This guide is designed as a comprehensive, long-form resource on intertextuality—a term that sounds academic, but is something we engage with every time we recognize a reference, a homage, or a twist on a familiar story.

Whether you’re a writer, reader, creator, educator, or just someone trying to make sense of modern media, this article serves as a star map through the rich and layered horizons of how stories talk to each other.

Here, you’ll find historical context, theoretical foundations, creative applications, and media-specific case studies, which are all designed to help you understand not just what intertextuality is, but how it works, why it matters, and how to wield it with intention.

This guide is for:

- Creators (writers, filmmakers, game devs, artists)

- Students and educators

- Pop culture analysts and critics

- Curious readers who love a good “Easter egg”

If you’ve ever asked, “Why does this story feel familiar?” You’re in the right place.

- Intertextuality

- How to Navigate This Article

- 1. Introduction: What Is Intertextuality?

- 2.1 Oral Tradition & Ancient Textual Echoes

- 3.0 Types of Intertextuality: The Many Ways Media Echo Each Other

- 4.0 Modalities Across Media Forms

- 4.1 Literature: The Proto-Internet of Human Experience

- 4.1.1 Classic Case Studies: Ulysses and Wide Sargasso Sea

- 4.1.2 Contemporary Novels (Neil Gaiman, Madeline Miller)

- 4.2 Film & Television

- 4.3 Comics, Graphic Novels, & Manga

- 4.4 Video Games

- 4.5 Music & Sampling

- 4.6 Visual Arts (Collage, Appropriation, and Artistic Dialogue)

- 4.7 Theatre & Performance

- 4.8 Advertising & Branding

- Conclusion… for now

How to Navigate This Article

This guide isn’t meant to be read all in one sitting (though you certainly can). It’s the size of a novella, and might be better digested in pieces. Use the table of contents to jump to the sections that most interest you.

Each central section also includes:

- Examples from literature, film, video games, and more

- Deep dives into key concepts and debates

- Toolkits and prompts to apply intertextual thinking

You’ll also find sidebars and appendices throughout for glossary terms, quick comparisons, and downloadables you can use in your own projects.

By the end of this guide, you won’t just recognize intertextuality, you’ll be able to read with it, write with it, teach with it, and most importantly, think through it.

Lastly, intertextuality is a concept that is continually expanding—just like the universe itself. So, we’ll be adding more to the guide as we sink our teeth into each topic and flesh it out. Be sure to check back often while we build the ultimate guide to this fascinating and mind-altering topic.

1. Introduction: What Is Intertextuality?

1.1 Hook & Definition of Intertextuality

What do Stranger Things, The Lion King, and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies have in common? More than you might think.

They’re all stories that carry the DNA of other stories—sometimes overtly, sometimes invisibly. This isn’t just about references or Easter eggs. It’s part of a much older, deeper phenomenon: intertextuality. It’s the idea that every story is, in some way, made of other stories.

Coined by literary theorist Julia Kristeva in the 1960s, intertextuality reshaped how we think about originality, authorship, and the broader narrative fabric. Today, it’s everywhere from remix culture and memes to genre tropes and cinematic universes.

But intertextuality isn’t just for critics or English majors. Understanding it changes how we write, how we read, and how we interpret the media we love. It’s the secret language of fiction that lets stories talk to each other across time, space, and media.

This guide is the Rosetta Stone you need to decode it finally.

1.2 “There Are No New Stories” – Nuanced Reframe

It’s common in today’s content-based landscape to hear “there are no new stories,” but the truth is a bit more nuanced and optimistic.

Every work of fiction—every novel, film, game, or comic—is part of a gigantic web of a superconscious interconnectivity that transcends social and political borders. It’s a web of influence, homage, genre convention, and cultural shorthand. Literary theorists call this intertextuality, but you don’t need a PhD to recognize it. You just need to have seen The Matrix, read The Hunger Games, or heard someone call a villain “Thanos-level.”

Kristeva’s work reframed storytelling itself. It suggested that meaning isn’t locked inside a text, waiting to be unpacked. Instead, meaning happens in the spaces between stories, in the echoes that ripple out into the universe, in what a work borrows, reshapes, or subverts.

In other words: fiction is a conversation, and we’re all part of it.

I, myself, can remember the first time the lightning struck me. I was an advanced English student in high school, but even after three years of near college-level study, it wasn’t until my senior year that everything clicked. My teacher at the time, Mrs. Turner, spoke of shared context—of allusions. Suddenly, the stories I struggled to glean deeper meaning from made sense, and it expanded my world tenfold. Hopefully, when you’re done reading this (however long it takes you), yours will be too.

1.3 Why Intertextuality Matters for Today’s Creators & Consumers

We live in an era where everything is “content,” and it moves faster than ever, thanks to advances in automation. To stay relevant and informed, it’s vital to build an understanding of how stories are created and why.

For creators, intertextuality is an incredible tool that can help you understand how stories echo across time, genre, and medium. This empowers you to work with greater intention. Whether you’re a novelist referencing Greek myth, a blogger toying with superhero tropes, or a game designer remixing sci-fi and folklore, intertextuality allows you to build layers into your work that reward your most discerning consumers, evoke emotional resonance, and spark recognition without requiring exposition.

For consumers, intertextuality turns media absorption into a game of cultural fluency. Recognizing an allusion, catching a reference, or understanding a thematic remix adds texture to every experience. Think of it as “DLC” for your brain. It creates an expanding web of reference that can make you feel more intelligent, cultured, and responsible for the mediums you regularly enjoy.

Above all, intertextuality is a means to orient ourselves in what has become an oversaturated content landscape. With so many stories competing for attention, it’s often the ones that speak in harmony with our existing knowledge that stand out. The ones that reframe what we already know in new and surprising ways. The ones that honor the past while pushing forward.

Intertextuality isn’t just about recognizing stories; it’s about understanding how we connect to them. And in a world defined by content, those connections matter more than ever.

2.1 Oral Tradition & Ancient Textual Echoes

Long before books, screens, or streaming services, stories lived on breath and memory.

Intertextuality began with oral traditions, in which stories were passed from mouth to ear and reshaped with each telling. Myths, folktales, and epics weren’t fixed in stone—they were living things, bending to fit the context of each new audience.

For example, a hero might gain a different flaw depending on the region. A moral might be sharpened or softened by the listener’s age. And the protagonist might have a few more close calls depending on how enraptured the audience was with the tale. These changes weren’t mistakes; they were all part of the art of storytelling perfected through the ages.

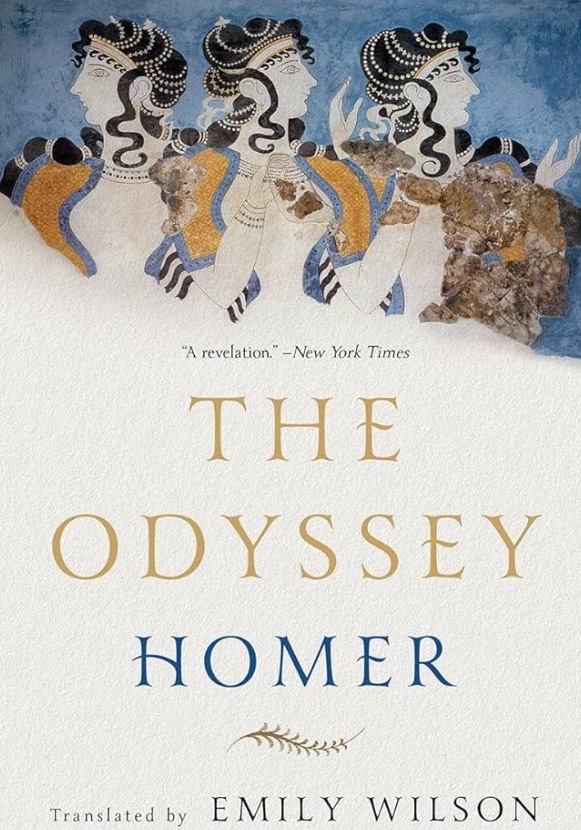

Take The Odyssey. Although we now read it as a static literary work, it began as an oral performance. It was sung, improvised, and regionalized. The story of Odysseus wasn’t told the same way in every city-state. What we think of as “the original” was already a remix of earlier heroic traditions, some possibly thousands of years older.

The same is true of religious texts. The Hebrew Bible, for instance, contains layered accounts and duplicated scenes not because of editorial sloppiness, but because it carries multiple traditions at once. Its echoes reach backward into oral lore and forward into centuries of reinterpretation.

In this sense, early intertextuality was less about citation and more about inheritance. Stories were communal. They weren’t so much “authored” as they were held, tended, and shared with the next generation.

Think of the concept like this: when a child asks for their favorite fairy tale again, they don’t want a perfect replication. They want your version. Oral storytelling, even now, permits us to reshape meaning in real time.

Intertextuality doesn’t begin in a library surrounded by dusty tomes. It starts around the fire, witnessed by friends and family.

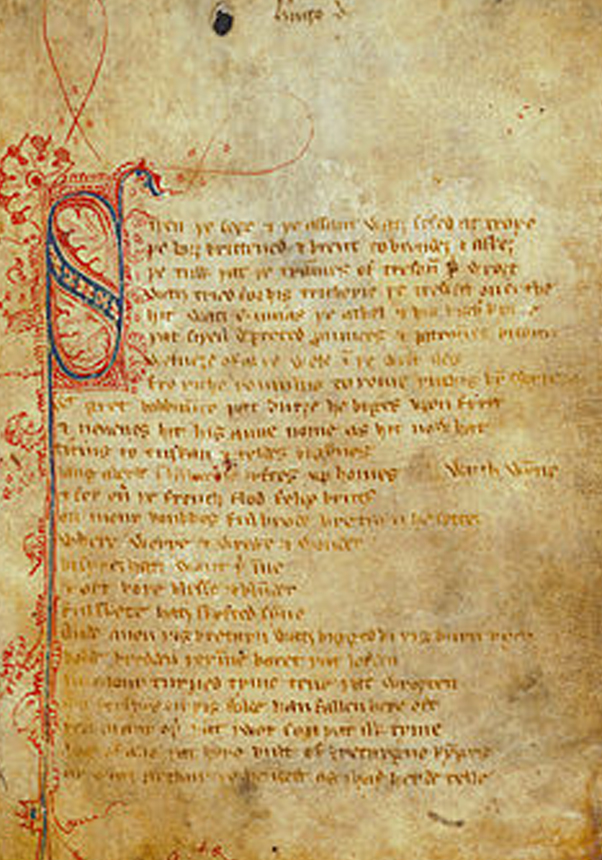

2.2 Classical & Medieval Practices

As stories moved from the oral tradition to the written page, they didn’t become less intertextual; they just began wearing their influences more openly.

In classical antiquity, Roman poets like Virgil, Ovid, and Horace built their reputations by reworking and referencing the works of their Greek predecessors. The Aeneid, for example, is not just a national epic; it’s a deliberate, intricate response to The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Virgil doesn’t hide this lineage. Instead, he leaves it strewn across the pages, inviting educated readers of the time to admire his ability to echo and expand upon Homer’s themes. In fact, being “derivative” wasn’t a stigma; it was considered a mark of literary excellence as long as you did it skillfully.

This spirit of creative echo continued into the medieval period, where intertextuality was not only common but often expected. Writers and scholars engaged with older texts through glosses—marginal notes that unpacked, questioned, or expanded upon the base text.

This wasn’t exactly “annotation” for the sake of explanation; it was a conversation that could be shared with every person who laid eyes upon the source material. It was also, in essence, a way for scribes to incorporate their own voice and dialogue into a piece and demonstrate established knowledge.

Medieval literature itself was a dense web of reference and retelling. For example, consider the Arthurian legends, which evolved over centuries through layering as they changed hands repeatedly.

From Geoffrey of Monmouth to Chrétien de Troyes to Thomas Malory, each new voice borrowed from the previous one and added their own cultural concerns. These weren’t reboots; they were iterative contributions to a shared mythos. Think of it as a giant, intelligent game of improv where “Yes, and” is the law.

Even theological texts, like commentaries on Augustine or the Christian Gospels, were interwoven with interpretations, counter-interpretations, and textual debates. Monastic and scholastic traditions thrived on the belief that no text was ever finished—only responded to.

Through these examples, you can clearly see how intertextuality in the classical and medieval world was worn on the sleeve. It was part of the process by which texts were produced, read, and shared. To these minds, writing was rarely about creating something new from scratch. Instead, it was about contributing to something that would endure through the ages as it was told, retold, edited, and discussed.

2.3 Early‑Modern Pre‑Theories (Shakespearean Borrowings, Cervantes’ Parody)

Before intertextuality had a name, it had practitioners.

One of the most prolific was William Shakespeare. Very few of Shakespeare’s plots were original. Romeo and Juliet was based on a narrative poem by Arthur Brooke, The Comedy of Errors was adapted from Plautus, and King Lear was drawn from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s chronicles. Yet Shakespeare’s genius lay in his ability to weave character, conflict, and theme so compellingly that the borrowed bones felt as if they were newly formed.

He didn’t just retell old stories—he elevated them.

Meanwhile, Miguel de Cervantes brought a different energy to early-modern synthesis. His Don Quixote is often credited as the first modern novel because it doesn’t just reuse tropes—it actively dismantles them. Cervantes parodies the romance genre by placing a delusional hero in a realistic, often hostile world. The result is both comic and cutting, a story aware of its predecessors and eager to challenge them.

In this era, we begin to see a shift from reverent replication to self-aware critique. Texts no longer had to uphold tradition—they could be shaken upside down to see what fell out of their pockets. General audiences could now laugh at and reinvent them.

The seeds of postmodernism had already begun to take root centuries before the term emerged. And with every new bloom, literature moved closer to understanding itself as a living web rather than a straight line.

2.4.1 Mikhail Bakhtin’s Dialogism

Mikhail Bakhtin was one of the first 20th-century thinkers to explore the nature of intertextuality, though he didn’t use the term himself. Instead, he offered the concept of dialogism. This is the idea that all language—and thus all literature—is fundamentally dialogic. That means it exists in response to, and in anticipation of, other voices.

To Bakhtin, no work of fiction stands alone. Even the most isolated novel is part of a web of ongoing conversations, shaped by social, cultural, historical, and ideological circumstances.

Sidebar: Another Look at the Philosophy of Bakhtin

Think of it this way: no two people are the same, even if they’ve had similar upbringings. Best friends share a language that no one else can understand, and the same can be said for families and strangers. There are specific universal experiences among human beings, from “the first kiss” to “the last breath.”

Does that mean that there is no meaningful way to think about these experiences because everyone has them at some point? Not at all. Because even when they’re the same in description, their context creates something wholly unique and beautiful. A point in time that can never be replicated again.

He believed that novels were the supreme example of dialogism because of their polyphonic nature. They contain multiple voices, perspectives, and discourses at once.

This is especially evident in the works of Dostoevsky, whom Bakhtin admired. In Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, he claimed that the characters presented in Dostoevsky’s works weren’t simply a mouthpiece for the author’s own ideas; they were crafted to embody different worldviews that inherently struggle against one another.

Speaking as an author myself, this method creates something that feels more true to life, something lived in. In the real world, there is no one “truth” that everyone can agree on when it comes to morality, governance, religion, or any of the myriad other topics that make up the web of human experience. And Dostoevsky doesn’t try to do that, he lets it be. This allows the text to offer a broader range of interpretations and stand the test of time.

Legendary Russian author tangent aside, Bakhtin’s vision of dialogism paved the way for later thinkers to reimagine authorship, originality, and literary meaning. It showed that stories aren’t solitary creations but polyphonic texts that participate in a vast, dynamic conversation.

He set the foundation, then Julia Kristeva gave it a name.

2.4.2 Julia Kristeva & the Coinage of “Intertextuality”

Julia Kristeva is the scholar who coined the term intertextuality. Building directly on Bakhtin’s ideas, she coined the term in her 1966 essay Word, Dialogue, and Novel, arguing that every text is a “mosaic of quotations” and that meaning is produced not in isolation but through the text’s relationship with other texts.

In her view, the boundaries between reader, writer, and text blur, and meaning emerges from their interactions.

Kristeva brought together linguistics, psychoanalysis, and semiotics to form a theory that language is not a closed system. Instead, it’s an ongoing process of exchange.

This marked a shift from structuralism (which sought to analyze systems of meaning) to poststructuralism (which questioned whether stable meaning existed).

One of Kristeva’s most important contributions is the idea that texts are shaped by a kind of cultural and linguistic echo chamber. No work exists outside this space. Even new creations are built from inherited codes, signs, and genres.

In her view, the text is less a creation penned in isolation and more a “node” in a dynamic network of relationships. In other words, nothing creative is ever made in isolation from its influences.

This helped reframe the concept of originality. Instead of being seen as a single author’s invention, originality could now be understood as the reconfiguration of existing signs and discourses. Thus, in a poststructuralist world, creativity lies not in creating something from nothing, but in transforming and recontextualizing what already exists.

Kristeva’s reframing of Bakhtin’s dialogism in Word, Dialogue, and Novel enabled intertextuality to extend beyond literature. It suddenly became a lens for analyzing all kinds of media, including film, art, and cultural productions.

From memes to modernist novels, Kristeva opened the door to understanding intertextuality as a fundamental condition of meaning-making.

Her theory didn’t just define intertextuality—it transformed how we understand communication itself. And surprisingly, most people were unaware it had a name.

2.4.3 Barthes, Derrida & Post-Structuralism

If Kristeva gave intertextuality a name, Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida helped tear down the last remaining walls around what a “text” is and who gets to define it.

Barthes’ famous 1967 essay, The Death of the Author, argued that once a text is written, the author’s intentions no longer matter. What matters is how readers interpret it. In his words: “It is language which speaks, not the author.”

This wasn’t just literary provocation—it was a power shift. Before post-structuralism, authors were seen as authoritative figures whose works carried fixed meanings.

But as literacy rose and media diversified, readers became more participatory. Barthes’ theory reflected that cultural shift. Suddenly, stories weren’t sermons handed down; they were conversations readers helped finish.

You can still see this tension today. Consider the Harry Potter series. Many fans now resist J.K. Rowling’s post-publication “clarifications” about character identities or world-building—not to mention their many criticisms of her antagonistic attitude towards the trans community, which paints her as an author who no longer believes in the core tenets of her own work.

In this light, the fandom has claimed stewardship of the story’s meaning, echoing Barthes’ assertion that the reader, not the writer, owns interpretation.

Derrida, meanwhile, pushed this even further. His concept of différance (a term that combines “difference” and “deferral”) claimed that meaning is never fixed—it always depends on context, contrast, and interpretation.

In his view, texts contain contradictions, gaps, and slippages that make them endlessly open to reinterpretation.

Taken together, Barthes and Derrida helped dissolve the idea of a singular, authoritative voice in any given piece of media. They emphasized the instability of meaning and the collaborative nature of understanding.

But this also raised important questions. For example, if authors don’t “own” their stories, who does? And when everything is interpretation, how can there be any objective truth?

Some argue that authorial intent can still matter. In some instances, such as Stephen King’s It, knowing the author’s rationale for controversial scenes, such as the “loss of innocence,” may provide necessary clarity. (Even if the answer is copious amounts of cocaine.)

In others, such as J.K. Rowling’s attempts to reframe her characters after publication, audiences often push back against claims that feel retroactive or disingenuous. The result? A world where the relationship between text, author, and reader is more dynamic and, at times, more contentious than ever.

All this to say, post-structuralism didn’t kill meaning. It just changed who gets to make it and the ultimate destination of the discourse around it.

2.5 Evolution in the Digital Era (Hypertext, Web 2.0, AI)

If post-structuralists cracked the foundation of stable meaning, the internet sent it into the Shadow Realm.

The rise of Web 2.0 in the early 2000s radically transformed the way media was created, shared, and engaged with. Suddenly, readers and observers weren’t just passive consumers—they were commenters, remixers, bloggers, creators, and critics. The line between “reader” and “author” blurred to the point of meaninglessness.

And with that shift came a tsunami of intertextual possibility.

Hypertext, once a fringe literary experiment, became the default mode of engagement. Every article, video, and social post could link, reference, embed, or reframe another.

Meaning was no longer contained in a single linear document—it spidered outward in infinite directions, making context more important than content and navigation more powerful than narration.

Meme culture emerged as one of the purest digital forms of intertextuality. A single image format can host thousands of variations, each riffing on the last, building on shared knowledge, cultural tropes, or inside jokes.

In this way, memes function like modern-day glosses—layered commentary on contemporary “base texts” such as celebrity scandals, political sound bites, or niche fandom drama.

But this explosion of meaning-making came with a steep cost…stability.

When everyone’s a creator, who becomes the expert? When all interpretations are valid, how do we protect truth? When stories move faster than they can be verified, how do we distinguish insight from misinformation—or worse, disinformation?

This is especially relevant in the age of AI, where content can be generated without human authorship. Language models trained on legions of intertextual material are now writing essays, poetry, advertising copy, and even screenplays.

Consider Indiana Jones. The series was famously inspired by early 20th-century adventure serials and pulp fiction—media that once dominated airwaves and matinees.

But for younger generations unfamiliar with those originals, Indiana Jones is the foundation. The homage becomes the hypotext. As time moves forward, even pastiche can be mistaken for origin.

In short, the digital age democratized intertextuality—and with that democracy came both brilliance and noise.

It amplified marginalized voices, enabled remix on a global scale, and turned every smartphone into a publishing house.

But it also challenged our collective ability to sift the meaningful from the manipulative.

Intertextuality has always been a living process. But in the digital age, it has become hyperactive. Is this a good and wholesome thing? Terrible and terrifying? The answer is, as Barthes and Derrida demand, in the eye of the beholder.

3.0 Types of Intertextuality: The Many Ways Media Echo Each Other

One of the most important things to note about intertextuality is that it’s not a single technique; it’s a toolkit. Some stories include subtle nods that only the most discerning readers will catch. Others remix their influences so loudly they practically shout them from the rooftops. The key is that intertextuality exists on a spectrum from delicate allusion to full-blown adaptation.

Here are some of the significant forms it can take:

3.1 Allusion

An allusion is a passing reference. It’s like a wink from one text to another. It doesn’t stop the story or explain itself. It’s just there, waiting for those who recognize it. Allusions enrich a story, but they don’t require explanation. If you catch it, great. If not, the story still works.

Think of The Simpsons, a show that’s built almost entirely on this kind of referential humor. In one episode, Lisa calls Ralph “The Chosen One,” evoking The Matrix without ever saying its name. These moments rely on shared cultural literacy for understanding.

But when the audience doesn’t share that context, things can get muddy. Just look at the rapid-fire references of Mystery Science Theatre 3000. The show is incredibly smart and doesn’t spend any time explaining itself. To the average TV viewer, MST3K may appear dull or confusing, but when you start to dig into its lexicon, it becomes much more enjoyable.

3.2 Homage

An homage is more intentional and reverent. It’s when a creator openly acknowledges their influences, often borrowing style, theme, or imagery as a tribute.

Quentin Tarantino’s entire filmography might as well be a love letter to genre cinema. His use of split screens, music cues, and stylized violence often mirrors the kung fu films, Spaghetti Westerns, and grindhouse flicks he grew up on.

And while they flirt with camp, they never cross the line into parody. Instead, they’re a celebration of all the things about the books, movies, and television shows he loves.

Another great example, and perhaps the gold standard of homage, is Star Wars (particularly Episodes IV, V, and VI). George Lucas drew heavily from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress and other samurai films, right down to mirroring their framing, costume design, and narrative archetypes.

If you’re in the know, you’ll see that Luke Skywalker’s garb is a stylized “gi,” a Japanese garb that folds over the chest, mainly used in martial arts like karate, judo, jiu-jitsu, and kendo. Even Darth Vader’s iconic helmet is shaped like a kabuto. So, they’re not just space wizards, they’re space wizard samurai.

In any case, Lucas didn’t copy Kurosawa, he honored him. And in doing so, he introduced a new generation to the spiritual DNA of a very different genre. Through intertextuality, Kurosawa’s influence can reach across time, subtly concealed by the mask of a space opera.

3.3 Parody

Parody and pastiche are two forms of intertextuality that are often conflated because they both involve imitation. However, they differ in tone, intent, and effect.

Parody imitates a work or genre to poke fun at it. It’s intentionally exaggerated. Sometimes it’s done lovingly, other times it’s laced with venom and poured into the glass of a local autocrat.

One of the earliest literary parodies is Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. While many will recognize the name through pop culture osmosis, context completely changes its meaning—in itself a consequence of intertextuality!

On the surface, it’s a story about a delusional old man who believes he’s a knight, attacking windmills he mistakes for giants. This is what most people remember. But underneath, it’s a razor-sharp critique of the idealized tales of chivalry that saturated Cervantes’ time.

Centuries later, we’re seeing something eerily similar happen with superhero media.

After almost two decades of cultural dominance by the Marvel Cinematic Universe, viewers have started to feel the strain. Enter The Boys, a savage parody dressed as a gritty drama. It doesn’t just spoof superheroes, it dissects them. Vought International, the fictional corporation behind its costumed ‘heroes,’ feels like Disney if it merged with BlackRock and ran its own cable news network. This creates a spectacle-state where branding, social media, and sensationalism blur the line between savior and sociopath. It’s Don Quixote but with more capes and blood.

Parody is also intertextual by nature. It needs a second text in the background—the thing being mocked. Without that context, parody can’t exist. But when it does, it creates meaning through contrast, which is where the laughter truly originates and why it is effective as a tool against oppression and cognitive dissonance.

3.4 Pastiche

If parody is made for laughs, pastiche is made for nostalgia.

Pastiche is also a form of imitation, but it does so out of love for the source material. It borrows the style, tone, structure, or aesthetic of earlier works to celebrate, reconstruct, or recontextualize them. It’s not trying to offer a critique of the source—it’s reconstructing the emotional core of what makes it special and bringing it to a new audience.

Stranger Things is a definitive example of this in modern times. It doesn’t just take place in the 1980s—it feels like the 1980s. From the synth-heavy soundtrack to kids arguing about Ghostbusters on walkie-talkies. It draws upon the elements that made the 80s a unique time in cinema—kids in danger, shadowy government labs, whimsical creatures, and supernatural spectacle.

Because of its incredibly effective use of pastiche, it’s no wonder it became such a commercial success, doing something that few Netflix shows ever do: end with a finished story.

The show weaves together references to Stephen King, John Carpenter, The Goonies, E.T., Firestarter, and more. But it doesn’t do this mockingly; it treats them with reverence. It uses their language (visual, emotional, and cultural) to tell a new story that captures the sincerity and openness of the period.

So, while references to a time period or genre are necessary for pastiche, it’s more about creating the atmosphere of the source than attempting to shove references together. If the worldbuilding and design choices you’ve made lead the audience to associate the work with the source, you have achieved an effective pastiche.

However, there are some pitfalls with this form of intertextualization that are easy to fall into. One of them is what has been dubbed “nostalgia-baiting,” in which the creator uses the setting to carry the emotional and contextual weight rather than the writing and storytelling.

Pastiche can be a powerful way to structure a story, but it should never constitute the entire composition of a work.

Sidebar: Forrest Gump and the Breakdown of Pastiche

Consider Forrest Gump—a film that positions its central character alongside significant moments in American history. Forrest’s proximity to real events gives the story much of its weight, even when the actual plot remains emotionally thin. What happens if you remove those historical callbacks? Would it hold the same resonance? This raises an essential question about storytelling: when does context do the heavy lifting, and when does the story itself need to stand on its own?

3.5 Adaptation

If pastiche pays tribute and parody pokes fun, adaptation rebuilds and transforms.

Adaptation is one of the most direct forms of intertextuality. It takes an existing work like a novel, myth, comic, film, or historical event, and reimagines it through a new lens. It may shift time periods, genres, locations, or cultural contexts—this turns the new work into a “reinvention” rather than a “repeat.”

One of the most beloved modern examples of adaptation is Clueless (1995), a bubblegum pink teen comedy that adapts Jane Austen’s Emma. It trades regency England for the halls of a Beverly Hills high school and corsets for crop tops and jeans, but the character dynamics and themes remain the same.

The film works because it recognizes that Austen’s exploration of self-deception, privilege, and growth still resonates with modern audiences. It contains many of the “universal experiences” that transcend time and speak directly to what makes us human…just with more slang and cell phones.

Adaptation isn’t always faithful—and it doesn’t have to be. In fact, some of the most successful adaptations are those that deconstruct or challenge the original. For example, The Green Knight (2021), directed by David Lowery, is a haunting and atmospheric adaptation of the 14th-century Arthurian poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Rather than simply retelling the chivalric tale beat for beat, it reimagines it. Instead of hope, justice, and clarity, the movie dwells in ambiguity, surrealism, and existential dread. The clear moral arc of the original is replaced with a meditation on fear, legacy, and the hollowness of heroism. This dark, moody, and at times maddening film dares to whisper, “The Roundtable is bullshit,” and somehow gets away with it.

Adaptations are at their best when they steal an emotional or intellectual truth from their source and translate it in a way that new audiences will understand. However, they don’t always have to play by the rules, and sometimes it’s best that they don’t. Reimagining a work is an invitation to new ways of thinking. It allows the creator—and the audience—to examine what they value, what they believe, and what stories deserve to be retold.

3.6 Remix & Mashup

Remix and mashup are possibly the messiest forms of intertextuality, but that’s what makes them fun!

In the internet age, there’s no escaping these. From rapid-fire meme cycles and TikTok trends to multiverses, fanfiction, and music, remix and mashup are the intertextual delicacies of choice for many modern media consumers.

And while it might seem like the concept emerged from the internet like some Rainbow Brite monstrosity, it actually has deep, ancient roots. The practice of reassembling, recontextualizing, and layering texts has been around since the written word was born.

Medieval scribes stitched together religious texts, poems, and folk tales with their own commentary. Shakespeare remixed myths, chronicles, and contemporary stories into plays that still dominate stages hundreds of years later. Postmodernists such as Warhol and Rauschenberg made collage their medium, turning repetition and reconfiguration into high art.

What has changed in the modern era isn’t the impulse; it’s the access, the speed, and the cultural recognition.

Remix today is everywhere. You see it in fan edits, in vaporwave albums built from chopped-up ‘80s ads, in films like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and in the way one meme format can host a hundred meanings in a single day. It’s not just a form of storytelling—it’s a form of cultural fluency, much like Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.

Mashup is intertextuality with the volume cranked up. It’s not subtle. It’s proud of its influences and often throws a tantrum unless you recognize the components. Then it knocks them over as soon as you do.

In this way, mashup shows how elements clash, merge, or subvert one another—sometimes in a shallow and pretentious way, other times in a humorous or even profound way.

To sum up, these forms of intertextuality are the most fluid and the least covert. Every visual, piece of text, or note is raw material waiting to be spun into something new, exciting, or foolish.

3.7 Metafiction & Fourth-Wall Breaks

To understand metafiction, you have to take a long look in the mirror until it winks at you.

This form of intertextuality refers to stories that are aware of their own status as stories. It’s fiction that comments on the act of storytelling, often exposing or playing with the devices that hold it together. When done well, it invites readers or viewers to question the boundaries between fiction and reality, narrative and truth, author and audience.

One of the most iconic examples of metafiction is Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, a novel in which the protagonist is the reader, attempting to read a book that repeatedly interrupts itself. Each chapter begins a new story that never finishes, leading to a layered experience where form and content become inseparable.

In film and television, metafiction often shows up as a fourth-wall break—when characters acknowledge the audience. Fleabag (2016–2019) uses this to hilarious and heartbreaking effect, letting the main character confide in the audience with knowing glances and whispered asides, only to later weaponize that intimacy in one of the most quietly devastating arcs in modern TV.

And then…there’s Deadpool, whose entire existence is a meta-commentary on superhero tropes. He not only talks to the audience, he criticizes his own writers, acknowledges his actors’ past roles (and kills them), and gleefully dismantles genre expectations while he himself is dismantled, usually with blades or lasers.

Metafiction often blends with literary self-parody, as seen in works such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. This semi-autobiographical novel features the author as a character and undermines its weighty anti-war subject matter with absurdism, time travel, and the repeated, fatalistic refrain: “So it goes.”

Metafiction can be a powerful storytelling tool when handled with care. But like any good hammer, it can be overused. Today, it seems like every large modern IP is driven to spill over the edge into a multiverse because the original bounds of its creation can no longer sustain new stories.

It’s hard not to see this as a failing of capitalistic greed that shackles creativity, but that’s a whole other discussion.

When done well, it encourages readers to engage critically with what they’re consuming. It reminds us that stories aren’t just entertainment—they’re constructs made of choices. Some of these choices are comforting. Others are confrontational.

Either way, when a story turns a mirror upon itself, it doesn’t just see its own reflection, it sees its frame, the reader, and everything that it is without.

3.8 Transmedia Storytelling & Expanded Universes

What happens when one story isn’t enough?

When creators seek to extend a fictional universe across books, films, comics, games, and even TikTok accounts, they enter the world of transmedia storytelling.

Unlike adaptation, which retells the same story in a new medium, transmedia storytelling disperses different parts of a single story across multiple platforms. Each one contributes a unique perspective, experience, or piece of lore.

At its best, this is where intertextuality becomes an architecture.

You’ve already seen it: Star Wars, The Matrix, Pokémon, The Witcher, The Walking Dead. These franchises have grown into entire ecosystems. You can read a novel, watch a series, buy a game, listen to a soundtrack, or attend an ARG-based scavenger hunt—all tied to the same fictional world.

But here’s the catch: not all transmedia storytelling is created equal.

Every entry in a transmedia universe should have the legs to stand on its own, or risk becoming a puzzle with missing pieces.

Many fans of The Rise of Skywalker were frustrated to learn that key plot details—like how Palpatine returned—were explained not in the movie but in a companion novel. That’s not expansion. That’s erosion.

When done well, transmedia can deepen and enrich a known universe. Consider The Animatrix, a 2003 collection of short films that expanded the Matrix universe. It wasn’t just an animated version of the trilogy, it gave new viewpoints, characters, lore, and artistic styles.

The Halo universe likewise grew through novels, live-action shorts, and in-game terminals, each adding emotional and narrative texture without requiring that gamers see everything to enjoy it.

However, when mishandled, as in the Five Nights at Freddy’s universe, transmedia strategies devolve into chaotic retcons and lore spaghetti. Creators try to inflate shallow ideas into sagas by treating fandom speculation as canon. The result? Confusion, exhaustion, and eventually, apathy.

This is not to say that there aren’t still things to enjoy in each entry—there absolutely are! It’s just important to view the things we love through a critical lens so that we aren’t taken advantage of as fans.

The potential of transmedia is enormous. Well-planned and executed expansions become vessels for intertextuality across media. They invite diverse creators to contribute, challenge audiences to see from new perspectives, and give characters lives that extend far beyond their original confines.

Speaking for myself as an author, transmedia is one of the most exciting aspects of intertextuality and fiction in general. Who wouldn’t love to see their work turned into a beloved empire that stretches across fandoms?

3.9 Easter Eggs & Fan Service

Easter eggs and fan service are like distant cousins to transmedia and a part of intertextuality that is often overused or misunderstood. It’s the difference between nodding to a reference and bribing the creators to include it.

These elements often reward attentive audiences with inside jokes, visual cues, quotes, or unexpected character appearances. But as with all tools, the way they’re used matters.

At their best, easter eggs and fan service can elicit genuine joy. They give viewers a moment of recognition—a spark of familiarity that feels like a reward for paying attention. When well-placed, these nods can deepen immersion, signal affection for the audience, or provide emotional resonance.

Think of Avengers: Endgame when Captain America finally says, “Avengers, assemble”—a moment built up over a decade of storytelling. Or when fans of The Mandalorian first saw Luke Skywalker reappear, de-aged and cloaked in green lightsaber glory.

These moments don’t just succeed because they’re nostalgic—they work because they’re narratively earned. But not all callbacks are created equal. Many modern IPs lean on these techniques out of habit, or worse, out of desperation.

Taking another Star Wars example with the same character, The Last Jedi is fraught with “what not to do.” Luke Skywalker has decades of history and belovedness as a character and Mark Hamill as an actor. However, in a single moment of “subversion” all of his narrative power is thrown away, literally, as he hucks Anakin’s lightsaber over his shoulder. If anti-fan service exists—this was that moment. And who can forget Poe Dameron’s “Your momma” joke?

Similarly, Star Trek: Picard has been criticized for bending entire plots to accommodate old characters, leaving new arcs underdeveloped and immersion disrupted. I know this because my wife hasn’t stopped yelling about it.

In such cases, fan service becomes a crutch. The audience is expected to cheer simply because a beloved character appears or a catchphrase is repeated, regardless of whether it makes sense in the story. This approach can erode trust, undermine worldbuilding, and turn meaningful storytelling into a checklist.

That said, fan service isn’t inherently bad. When wielded with purpose, it’s a way to honor fans, acknowledge community, and pass emotional torches.

But when it’s used as bait to lure audiences into content that lacks meaning or merit, it reveals the tension between art and commerce. To put it bluntly: intertextuality becomes exploitation when it asks for applause instead of offering depth.

That doesn’t mean we have to become cynical. It simply means we need to examine these moments with both our hearts and our critical minds. Don’t let the greed of those who own these IPs come between you and having a good time.

3.10 Intertextual Irony & Subversion

Sometimes, the most powerful intertextual moments aren’t callbacks, tributes, or memes—they’re landmines. Irony and subversion play with audience expectations not to flatter them, but to destabilize them. When used with care, they expose universal truths, critique tropes, or reflect the messiness of the real world. When used poorly, they just make people want to burn it all down.

Subversion is most effective when it’s done with intention—when the breadcrumbs are laid carefully, and the audience is rewarded for paying attention. Ideally, it should shock some and satisfy others. It operates like a conspiracy, not in the sense of being hidden, but in that it becomes visible only after everything clicks into place. And in fiction, that click has to feel earned.

Game of Thrones, the once-upon-a-time cultural phenomenon based on A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin, offers famous (and infamous) examples. Arya Stark’s abrupt victory over the Night King defied many fan theories, but it was still rooted in years of character development. On the other hand, Daenerys Targaryen’s sudden turn to madness in the show’s final stretch felt unearned to many. It was less like a twist and more like a betrayal. Subversion only works when it grows organically from what came before.

Irony, meanwhile, can be both poignant and painful. Blade Runner 2049 serves a quiet, brutal twist when K—believing he’s found love in his AI companion, Joi—sees a massive billboard version of her addressing him by name. What he thought was personal was never unique. The irony runs deep, not for the joke, but for a heartbreaking scene that leaves the audience haunted.

In today’s media-saturated world, subversion has become a kind of creative arms race. With countless thinkpieces, Reddit threads, and fan theories circulating before a finale even airs, the pressure to surprise audiences has never been higher. But creators often mistake surprise for satisfaction. If they twist too far and ignore the logic of their own world just to be unpredictable, their subversion becomes sabotage.

That doesn’t mean irony and subversion are fads. They’ve always been part of the storytelling toolkit because they’re part of how we experience life. How often have you expected one thing, only to receive another? Whether it’s a happy anodyne or a bitter pill, it’s how stories can challenge us, disarm us, or hold up a mirror to our assumptions.

But like all intertextual tools, these should be wielded with care. Irony should illuminate. Subversion should deepen. And if you’re going to pull the rug out from under your audience, make sure you show them the edge of it first!

4.0 Modalities Across Media Forms

As we’ve touched on before, intertextuality doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Texts and other media are shaped by what came before them. In this section, we’ll discuss another way it can be altered—the medium through which the story is told.

Books, films, music, games, and social media each have distinct strengths, limitations, languages, and audiences. And these differences aren’t just aesthetic; they deeply affect how intertextuality is delivered to the audience.

Think of this concept like sound waves. When sound travels through air, it does so at a different wavelength than it does through liquids or solids. The wave is the same when it comes from the source, but when it enters a different medium, it’s fundamentally changed.

The most obvious differentiator is access. Movies are arguably the most accessible form of storytelling (unless a person is visually impaired), followed by games, books, and, finally, music, particularly more conceptual or abstract compositions. This accessibility often determines how widely intertextual meaning can be shared or received.

But each form also has its own internal language—the grammar of camera angles, panel layouts, sampling techniques, branching dialogue trees, or meter and metaphor. These mechanics dictate not just how stories are told, but how they can nod to or borrow from others. A comic book wink isn’t the same as a film homage, and a musical quotation hits differently than a novelistic allusion.

Books are arguably the most fertile ground for intertextuality. They’ve existed the longest, evolved the most slowly, and built traditions upon traditions for thousands of years. Their depth and flexibility allow for intertextual moves that are often subtle, layered, and rich with resonance.

Music, on the other hand, is the origin point of remix. Sampling, quoting, reusing motifs, and adding effects—these practices are as old as the medium itself. But because music is so abstract, its intertextuality often depends on context, culture, and history more than literal references. That can make it harder to spot, but no less powerful.

Games are the most immersive medium mankind has ever created. They allow the player not only to witness a world but also to interact with it, shape it, and even break it. This opens up entirely new forms of intertextual engagement from in-world references to player-authored emergent narratives.

Film and television are perhaps the most heavily authored media where a director or showrunner’s vision dominates. While intertextuality can still emerge organically, it often reflects intentional decisions rather than collaborative accidents. In that way, “death of the author” is a harder sell on screen than on the page.

The story may be the same, but how it’s told, who tells it, and how it’s received make all the difference.

4.1 Literature: The Proto-Internet of Human Experience

Why does literature remain the backbone of intertextuality?

Because it’s the most democratic, enduring, and adaptable storytelling form we have.

You don’t need a studio, a production team, or expensive software to make a book. You need thoughts, something to write with, and a surface to inscribe on. In that sense, literature is the most accessible entry point to creation—and it’s been that way for thousands of years.

While music and art may have come first in the form of song or cave painting, literature prevails in its ability to preserve, refine, and transmit meaning. It became the first medium capable of archiving complex human ideas. Because language is its primary tool, it transcends the limitations of time, location, and material.

Literary works become nodes in a vast intertextual web. They capture the real and the imagined, the sacred and the profane, the historical and the mythical. And over time, these nodes form the basis for entire cultural conversations—ones that echo for generations.

In this way, literature functions like a proto-internet: a shared space where human emotion, philosophy, absurdity, and aspiration all mingle and evolve. When a modern author references Homer, Shakespeare, Dickinson, or Baldwin, they’re not just quoting—they’re syncing up with this web. They’re adding layers to meaning, drawing power from the texts that came before, and passing that power forward.

And the beauty is, you don’t need to have read every classic to feel the weight of this tradition. You just need to know that every word on the page was shaped by the words that came before it.

4.1.1 Classic Case Studies: Ulysses and Wide Sargasso Sea

What does it mean to write back to a text, not just write from scratch?

Think of it as replying to a letter. You read the thoughts of the sender, whoever it may be, interpret their words, and then send a message back that’s shaped by your thoughts and emotions.

If storytelling is a conversation, then the texts mentioned below are responses—ones that may challenge, expand, or even contradict the author of the original work. And like any reply, they’re shaped by tone, perspective, and cultural bias.

This is the essence of intertextual literature. It continues a message rather than derailing it.

Take James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), for instance. On the surface, it’s a story that details a single day in the life of Leopold Bloom as he wanders through Dublin. But beneath that, it’s a reimagining of Homer’s Odyssey. Joyce transposes Homeric heroism onto the mundane, turning grand adventure into grocery lists, pub stops, and the quiet complexity of ordinary life.

By drawing parallels between Bloom and Odysseus, Joyce isn’t trying to just copy epic structure. Instead, he’s showing that mythic journeys still happen, even if they take place in tenement flats and city streets. His novel becomes a modernist mirror, reflecting the grand shapes of mythical storytelling in a city skyline.

Now look at Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys.

Where Joyce boiled myth down to its essence, Rhys interrogated a canonical British novel: Jane Eyre. Specifically, she gives voice to Bertha Mason. In the novel, Bertha is known as the “madwoman in the attic.” But by imagining her life before she became Rochester’s imprisoned wife, Rhys deepens the character and grants her some justice through empathy.

Rhys’s novel is a direct intertextual act of reclamation. It reframes Bertha (renamed Antoinette) not as a monstrous figure, but as a woman trapped between colonial violence, cultural erasure, and patriarchal control. In doing so, Rhys doesn’t just speak to Brontë—she challenges both the author and the ideals she was handed to pass along.

This is where intertextuality becomes a moral act.

A great literary response doesn’t just tread the same spaces as the original. It restores lost voices and tells new stories within the margins. Sometimes, it surpasses the original by revealing the truths the earlier author could not—or would not—see.

Retellings and replies like these remind us that literature isn’t a static canon. It’s a living exchange across time, one where every reader, writer, and reimaginer has a seat at the table.

4.1.2 Contemporary Novels (Neil Gaiman, Madeline Miller)

Why are modern readers drawn to retellings?

Part of it is simple—we want more of what we love! Myth, folklore, and classical literature still hold immense cultural power, but many of these works were written at different times, with different values, and in dialects or styles that now feel impenetrable or even gate-kept from a general audience.

That’s where authors like Neil Gaiman and Madeline Miller come in.

Gaiman’s American Gods (2001) is a masterwork of mythological remix. He doesn’t just adapt old stories—he brings them to life, dragged across continents and time itself. Within the asphalt veins of modern America, he injects Norse, Egyptian, Slavic, and African deities, bringing with them all their faults, magnified by centuries of emotional baggage.

What results is both a reinvigoration of ancient lore and a biting critique of modern worship: media, celebrities, capitalism, and technology. The gods endure because people believe in them. But what does that say about us? Are the same humanistic patterns that kept our ancestors restrained by dogma enslaving us as well?

Sidebar: Ethical Consumption & Creator Accountability

It’s always important to consider the people behind the stories we admire. While Neil Gaiman remains a highly celebrated author, discussions around creator accountability, especially in literary and fandom spaces, are ongoing.

At the time of writing, there are no verified allegations of sexual misconduct against Gaiman. Still, readers are encouraged to do their own research, reflect on their values, and consider how they engage with art and the people who make it. If any new information surfaces regarding the truth behind these rumors, we will update our guide accordingly.

Art does not exist in a vacuum. And neither do the artists. At Fictionphile, we will always side with the victims of abuse while the truth is litigated.

Similarly, Miller’s The Song of Achilles (2011) and Circe (2018) offer a more emotionally intimate lens. Rather than focusing on war and conquest, Miller gives voice to characters long flattened by patriarchal myth-making.

Circe, often reduced to a footnote in The Odyssey, becomes the protagonist of her own journey in all of her flawed, brilliant, and profoundly human glory. Likewise, The Song of Achilles shifts the focus of the Iliad to the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles rather than the spectacle of war, giving us a profoundly

emotional and unabashedly queer tale.

These novels succeed not just because they retell old tales, but because they reinterpret them. They speak to today’s readers with updated language, deeper emotional nuance, and greater ethical awareness.

In doing so, they create a bridge between the archaic and the contemporary—between dusty texts and living meaning.

4.2 Film & Television

Film and television are inherently intertextual, often more so than they appear at first glance.

This is because, unlike novels or plays, which rely on text and imagination, visual media uses an incredibly broad toolkit. Think camera angles, lighting, music, costume design, actor performance, editing choices, and even marketing strategies.

All of these elements can carry references, mirror other works, or consciously engage with their predecessors. As a result, film and TV have the ability to subliminally evoke intertextuality in a way that other media can’t.

For example, genre itself is a kind of intertextual framework. As soon as a film opens on a barren landscape with a lone rider, or a detective walks into a smoky room in a trench coat, the audience already knows what kind of world they’re entering.

Genre cues like these aren’t just a convenient vehicle for convention; they’re also an incredibly effective shorthand for audiences to follow to glean understanding. They tell us what emotional and narrative patterns to expect by echoing hundreds of other works in the same vein.

But when a film disrupts those expectations or blends them together, it can be equally as powerful and informative. Two great examples of this are Ethan and Joel Coen’s No Country for Old Men in which the hero was stripped from the narrative and Ridley Scott’s mixture of noir tropes with cyberpunk and dystopia in Blade Runner. By defying and grafting genre patterns in cinema, the intertextuality deepens.

Visual media are also particularly well suited to pastiche because their form is instantly recognizable. A scene shot with a handheld camera with washed-out colors might evoke war documentaries, even if the subject is fictional. Meanwhile, a symmetrical wide shot might recall Wes Anderson before a word of dialogue is even spoken.

These visual references create an almost telepathic conversation between creators, viewers, and every work that their minds can conjure.

In modern franchises, this tendency has reached a new level. Properties such as Westworld and Fantastic Beasts rely on engineered intertextuality to generate interest and advance the shared narrative. All the callbacks, cameos, universe-expanding plot twists, and recycled lines operate both as bait to lure consumers and as a reward for the attentive.

When done well, as in the early seasons of Westworld, these payoffs can feel earned because the groundwork has been carefully laid. But when handled poorly, as with later entries in the Fantastic Beasts series, they can feel hollow or, worse, pandering.

The problem with engineered intertextuality arises when creators assume recognition is enough to satisfy. In reality, reference without resonance leaves emptiness in its wake.

Beyond the West, cinema engages intertextuality in different ways. Films such as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and RRR reinterpret myth and history through their own visual vocabularies.

The Matrix, now considered a modern myth in its own right, drew from anime, cyberpunk novels, and Hong Kong action films. Likewise, anime often borrows from both Western media and Japanese folklore, blending—at times—conflicting narratives and aesthetics. In this way, global film traditions speak to one another across cultures and genres, sometimes whispering, other times shouting right in your ear.

What ultimately sets film and television apart is their capacity to layer intertextual meaning quickly and effectively. Visual cues, sound effects, a line of dialogue…each one can activate a whole network of associations. But this strength is also a weakness in a sense. Because when everything is a reference, nothing is. Intertextuality works best when it enhances story and character, not when it replaces them.

4.3 Comics, Graphic Novels, & Manga

Comics are one of the most overlooked (and most potent) arenas for intertextual storytelling.

Unlike literature, which relies solely on language, or film, which demands massive production budgets, comics combine the strengths of both. Their fusion of image and word allows creators to make bold stylistic choices that instantly evoke meaning. A single splash page can carry more intertextual weight than ten minutes of screen time or a thousand words of prose.

This is especially true when you consider the medium’s culture of serialization, crossover, and self-reference. In Western comics, superhero universes such as those of DC and Marvel have spent decades developing internal mythologies. These are entire ecosystems of characters, histories, and alternate realities that are constantly blotted from existence, rebooted, or folded back onto themselves.

In this paper jungle, intertextuality becomes a tool of survival. It allows characters to die and return, swap universes, merge timelines, and argue with their writers. Over time, these became more than simple plot devices; they became a formal part of the medium’s lexicon, allowing those in the know to engage on a deeper level.

The Deadpool comics exemplify this perfectly. Before he was a household name, thanks in major part to Ryan Reynolds’ portrayal of him on the screen, Deadpool was already a meta-fictional disruptor.

He didn’t just break the fourth wall—he hollowed it out and made it into an evening chair where he could eat chimichangas and sip desert pear margaritas. This allowed him to reference the conventions of the genre, his creators, and even acknowledge the fans reading the panels.

However, creators don’t need a fourth-wall-breaking character to reflect on and critique real-world ideologies. Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons exemplifies a darker mode of intertextuality that co-opts the superhero genre to dissect Cold War paranoia, authoritarianism, and moral ambiguity.

Though comics have long been associated with caped crusaders of all kinds, their intertextual reach goes much further. Graphic novels like Maus by Art Spiegelman use intertextuality to reinterpret history itself, blending memoir, metafiction, and allegory to depict the Holocaust through anthropomorphic characters. Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, in the same vein, blends personal memory with Iranian political history to tell a story about growing up in a cultural revolution.

Titles like Saga, Something Is Killing the Children, and Monument rework fantasy and horror tropes, layering in commentary on gender, war, trauma, and power.

Meanwhile, in Japan, manga embraces cross-medium references and cultural intertextuality with equal complexity. One Piece, for example, builds its world through references to history, folklore, and even other rival manga. Series like Bakuman and Gintama function almost entirely as love letters (or sarcastic jabs) at the manga industry itself.

Then there’s Berserk by the late Kentaro Miura. The work has had such a profound influence on modern media—especially video games and fantasy works—that it has almost become a hypotext in its own right.

The biggest takeaway from comics and manga is that because they are less constrained by the economics of film and television, they can take bolder risks.

Creators can reboot, remix, and reinvent with far less friction. That freedom has turned comics into one of the richest intertextual mediums we have, both in how they draw from other sources and in how they reflect upon themselves.

In short, comics don’t just use intertextuality. They are made of it.

4.4 Video Games

Video games transform intertextuality from a solid into a liquid. The story is no longer static—it bends with the player’s decisions, stumbles, and discoveries. Every jump missed, puzzle solved, side quest triggered, or town burned to the ground changes how the story unfolds and how the intertextual references are received. It is narrative in flux.

Unlike books or films, which are received in relatively linear, passive fashion, games require input. The audience becomes a collaborator, and that makes intertextuality a participatory experience.

Some of this intertextuality is narrative. Think of the countless games that reimagine Journey to the West—from Enslaved: Odyssey to the West to the recent Black Myth: Wukong. The source material is bent and reshaped to fit different gameplay modes and visual aesthetics, but it remains visible, like a mythic skeleton underneath.

But intertextuality in games also shows up in mechanics, genre language, and culture. When someone says “first-person shooter” or “Metroidvania,” we already know what we’re in for: checkpoints, level design philosophies, control schemes, and even HUD layouts. This kind of embedded literacy creates shared expectations that developers can either lean into or subvert.

Even failure contains meaning. Missing a timed jump in a platformer or triggering a bad ending in a branching narrative game isn’t just a gameplay moment—it’s a point of divergence, an echo of similar systems in other games that make you think, “Ah, this is like Undertale,” or “That’s classic Dark Souls.”

Franchise identity adds another layer. Every Final Fantasy title, for instance, stands alone in story and setting, but certain visual motifs like chocobos, summons, Job classes, musical cues, and even philosophical themes return across iterations. The result is a kind of intertextual resonance chamber—a shared dream experienced differently each time.

And then there are games like Dragon’s Dogma and Dragon’s Dogma 2, which start as traditional fantasy action RPGs and slowly unravel into something mythic, metaphysical, and meta-textual. The second game, in particular, twists itself into meta commentary so deep it requires thoughtful analysis to even perceive. (For a breakdown of just how deep this rabbit hole goes, see Punk Duck’s “Dragon’s Dogma 2 Isn’t What You Think It Is.”)

Games are also deeply intertextual because they’re collaborative by nature. They fuse writing, visual art, music, sound design, and programming into one experience. That makes them ideal playgrounds for remixing myth, memory, genre, and meta-commentary.

Interactive storytelling, in this sense, is a return to something ancient: the fluid, responsive magic of oral tradition. But instead of a storyteller on a stage, we have engines, interfaces, and millions of branching possibilities. This isn’t just a new kind of storytelling—it’s a new kind of text.

In the best cases, an intertextual game isn’t just one that references other works—it’s one that understands its own design language and uses it with intention. Whether chaotic or controlled, elegant or absurd, the logic of the world must hold together. If it does, games can pull off a level of intertextual synthesis no other medium can match.

4.5 Music & Sampling

Music is emotion rendered audible, and like every other form of media, it too is deeply intertextual. However, its depth often comes through in ways that are felt in the soul rather than the mind.

Unlike visual or literary references, musical intertextuality operates in a realm of sensation. A few notes can summon whole lifetimes of memory. A chord progression can recall an era. A sampled lyric or melody doesn’t just draw upon nostalgia—it makes you feel it.

Some listeners may cry theft when a song borrows from another, but most don’t. Most of us feel smart or emotionally connected when we recognize the echo. Because of this, music is one of the most powerful and immediate delivery systems for intertextuality. It doesn’t beg you to analyze, it asks you to listen.

Sampling, remixing, and quoting are as old as music itself. Folk songs evolved through generations by being borrowed and reshaped. Jazz musicians build entire improvisations on the bones of earlier compositions. Classical composers like Mahler and Shostakovich inserted coded references to their own or others’ work as political, religious, or emotional commentary.

In the modern age, hip-hop brought sampling to the forefront—both as a tool of artistry and a flashpoint of legal battles. Producers like J Dilla, Kanye West, and DJ Shadow built new soundscapes by digging through old records, chopping and looping fragments into something completely fresh. The past becomes the raw material of the present.

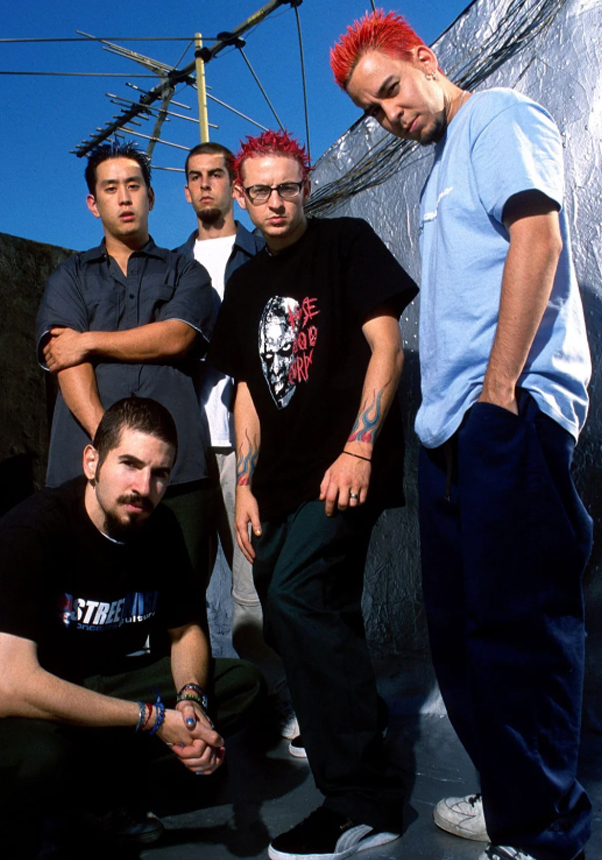

Take Linkin Park’s A Thousand Suns, for instance. It’s a masterclass in musical intertextuality. The album blends nu-metal with electronic textures, spoken-word political samples, ambient transitions, and lyrical allusion. The result feels less like a collection of songs and more like a singular narrative arc—an emotional tapestry stitched from influences both obvious and hidden. It doesn’t just sound good. It says something. It carries truth…one that may be more resonant today than ever before.

That’s the heart of musical intertextuality: resonance. You don’t need to understand musical theory to “get it.” You can just vibe and bring all of your experiences into the sound to swirl and soak and dance.

Through music, you can hear an artist’s history, their record collection, their culture, and their rebellion while ruminating on your own. This layering is what makes music so universal and yet so personal. What speaks to one listener might go unnoticed by another. But the beauty lies in how a sound can speak across generations, genres, and geographies. It truly is a universal language.

Ultimately, music reminds us that intertextuality doesn’t need to be cerebral to be profound. Sometimes it’s as simple as a few chords echoing through your headphones and making you cry.

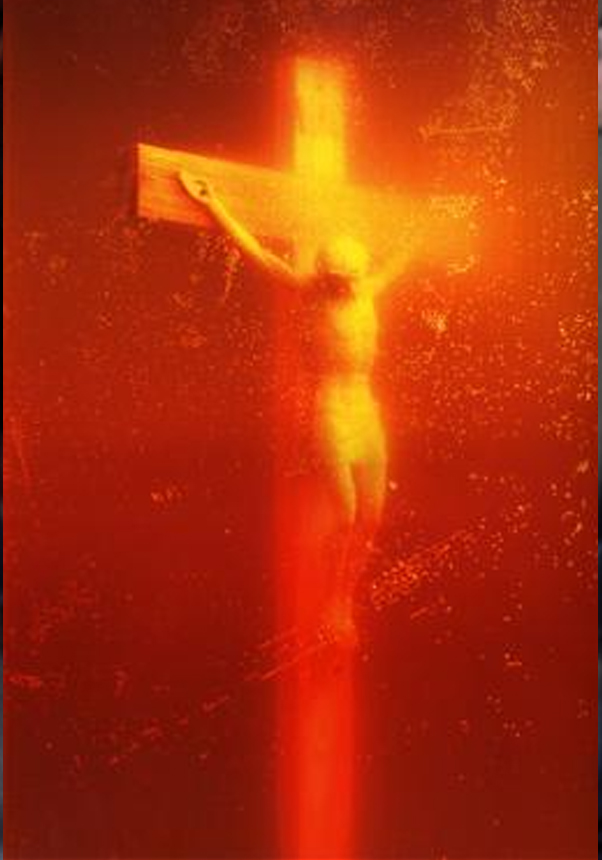

4.6 Visual Arts (Collage, Appropriation, and Artistic Dialogue)

Visual art may be the most openly intertextual medium of them all—partly because it often wears its influences on its sleeve, and partly because its meanings can be layered, elusive, or even contradictory.

In painting, sculpture, and collage, intertextuality emerges through mimicry, homage, inversion, and rebellion. Some artists revive classical styles as tribute or critique. Others go the extra mile to create pieces that carry on a conversation (or a knockdown, drag-out fight) with art itself.

Take the infamous Piss Christ byAndres Serrano or Banksy’s self-shredding painting Love Is in the Bin (2018). Some see these pieces as pretentious, but if you dig a bit deeper, you’ll see that they’re intertextual statements. They ask things like, “What is art?” “Who decides?” “Can meaning survive destruction?”

At the same time, artists like Kehinde Wiley reframe Renaissance portraiture by painting modern black subjects in heroic poses, directly referencing, and subverting, European art traditions. His work functions as both homage and critique, pulling old visual languages into a new cultural context.

Even pigments tell stories. The feud between Anish Kapoor and Stuart Semple over exclusive color rights (such as Vantablack and its cheerful “Pinkest Pink” rival) turns material science into an art-world meme. It’s an intertextuality fueled by chemistry, commerce, and spite.

Then there’s collage and mixed media, one of the most literal forms of remix. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Barbara Kruger stitch together found images, text, and cultural symbols to make new statements. The juxtaposition of styles, eras, and media becomes the message in the mosaic.

Modern artists may not always display their references on big neon billboards, but that doesn’t mean their work is any less intertextual. In fact, you can find the echoes in every piece from its style, technique, and medium.

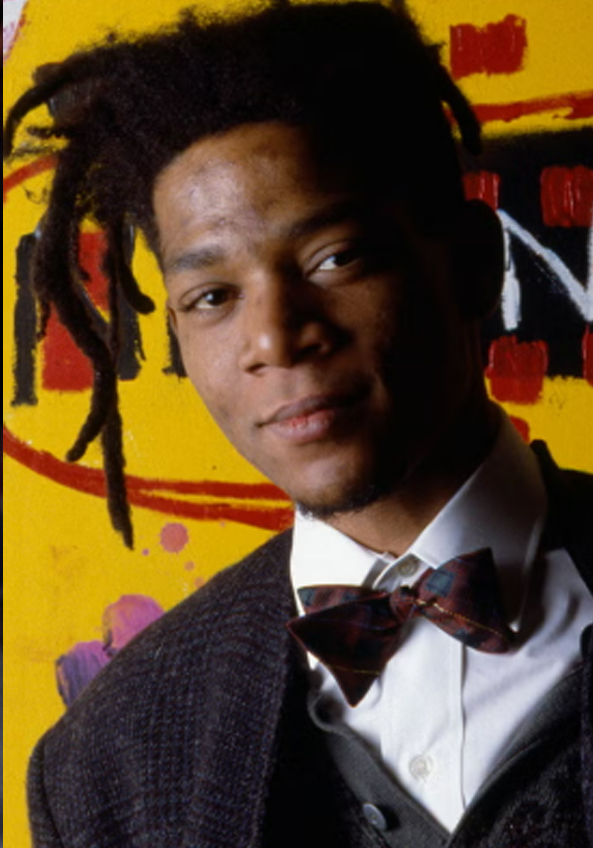

A minimalist square can invoke Kazimir Malevich. A chaotic spattering of colors might nod to Jackson Pollock. Even outside of galleries and public halls, graffiti tags participate in a tradition of call-and-response across concrete canvases. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat took this visual language further, blending street art with neo-expressionist and classical references to produce work that echoedPicasso while fiercely asserting its own identity.

Aside from direct references, a large share of visual art’s power lies in its ambiguity. Unlike film or text, a painting doesn’t have to guide you from A to B to be successful. It can simply exist, leading your thoughts to wander and put together a story of your own making, shaped entirely by your experiences.

Whether through rebellion, reverence, or pure creative instinct, visual art offers a sprawling space for intertextuality—one where even a brushstroke can carry a subliminal connection to the web of shared stories we inhabit.

4.7 Theatre & Performance

There’s something ancient and electric about live performance that no camera, screen, or page can fully capture. In theatre, intertextuality comes alive through the body, the voice, the space, and all the unpredictable elements that constantly swirl in and around the stage.

Unlike film or literature, theatre is a communal event. The audience breathes the same air as the actors. There’s no post-production safety net when the spectacle is live, which means every performance is inherently unique. A missed cue, a scenery wobble, an audience reaction—these disruptions don’t break the experience—they’re a part of it.

Intertextuality in theatre often emerges through its layered traditions. From ancient Greek choruses to Broadway musicals, the medium carries centuries of accumulated storytelling DNA. Even its slang is steeped in intertextual context. For example, “break a leg” is a superstition that seems to be ingrained in society like a spell. And who could forget “theatre kid energy,” which has become a meme shorthand for a very particular kind of expressive exuberance?

Modern stagecraft weaves together multiple disciplines, from writing and acting to costume design, set construction, sound engineering, and choreography. Each of these, in turn, can become a channel for reference or reinvention. Think Hamlet, but it’s set in space, or a gender-flipped version of Death of a Salesman. Every production is a new conversation ripe for exploration of different themes, motifs, and settings where imagination can run wild.

Theatre doesn’t have to be a one-way discussion either. Sometimes, the audience is invited to join in on the conversation. One of my favorite venues, Pocket Sandwich Theatre, has made a tradition of parodying famous works with intentionally campy melodramas. Audiences are encouraged to boo, cheer, and even throw popcorn at the stage. This participatory chaos transforms the audience into co-creators—breaking the fourth wall in a way that’s joyful, local, and deeply human.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have the spectacle of Broadway and Cirque du Soleil—productions that push performance to the outer limits of art. These shows blend opera, clowning, dance, illusion, and mythology into layered, sensory-rich experiences. Each one draws from global traditions while becoming a cultural text in its own right.

For those who’ve had the privilege of participating in live theatre, the experience is both deeply personal and profoundly communal.

In high school, I performed in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and The Music Man. It didn’t matter that the sets were simple or the notes were occasionally off-key. The audience was made up of people in our community. Friends, family, teachers, and patrons of the district all gathered to spend an hour or two enjoying the show.

That’s the secret of theatre’s staying power. It’s one of the few mediums that’s always accessible. Anyone can stage a puppet show or direct a musical down at the local recreation center. You don’t need a studio or a publishing deal, just a script, some courage, and a willing audience.

In the end, theatre is intertextual because we are. It’s a tradition that goes back to the earliest days of human interaction and it’s ingrained in all of us from birth. From the moment you turn your tree house into a pirate ship headed for a storm and all your friends pretend with you, you’ve become a part of it.

4.8 Advertising & Branding

Have you ever cringed at a fast food chain using a meme on social media? There’s a reason for that.

In a world saturated with content, brands are desperate to stand out, and intertextuality has become one of their sharpest tools. Cultural shorthand—memes, slogans, viral dances, nostalgic callbacks—is easily recognizable, emotionally potent, and endlessly remixable. By co-opting popular formats and tropes, companies can bypass traditional marketing strategies and tap directly into cultural conversations.

At its best, this strategy feels clever and responsive. Wendy’s X account, for example, gained attention for roasting other companies and leaning into internet sarcasm, which aligned perfectly with its fast food, fast laugh persona. The result? Viral engagement and a brand identity that felt less corporate and more like a snarky friend.

But not every brand can pull this off. When a corporation like Walmart tries to insert itself into meme culture or adopt Gen Z slang, it often comes off as tone-deaf. It’s the marketing equivalent of Steve Buscemi asking, “How do you do, fellow kids?”

The disconnect usually stems from a lack of authenticity. Brands aren’t people. They’re legal entities trying to sell you things. When they try to establish parasocial relationships with consumers by mimicking human interaction—especially through humor or emotional appeals—they risk undermining their credibility. What’s worse, they may trivialize real issues in the process, especially if they attempt to memeify topics like worker treatment, sustainability, or social justice.

That’s not to say brand intertextuality can’t work. When done with clarity, respect, and alignment to audience expectations, it can create powerful associations. For instance, Nike’s use of intertextuality through slogans like “Just Do It” becomes a kind of cultural scaffolding—one that’s easy to build new meaning around, from inspirational ads to activist campaigns.

In the end, brand-based intertextuality is a high-risk, high-reward game. It can make corporations feel more relatable—but it can also lay bare just how hard they’re trying to seem human.

When a meme hits, it feels effortless. When a brand tries to hit a meme, it often feels like a boardroom was involved. And nothing kills a punchline like a quarterly report.

Conclusion… for now

Intertextuality isn’t a garnish. It’s the broth.