If you ever loved a movie, play, TV show, or book–anything with dialogue–take a moment and thank Aeschylus.

Aeschylus? That ancient Greek playwright you haven’t thought of since you were forced to read a university press copy of one of his plays in 11th grade Literature? You likely read Aeschylus’ plays alongside those of Euripides and Sophocles.

Yes, that Aeschylus!

Unconvinced of Aeschylus’ impact on modern theatre, plays, and drama at large? Take a moment and participate in our thought experiment.

Dialogue: Drama’s Driving Force

Put aside Aeschylus for a moment and imagine your favorite movie. Hold it out in your mind.

Say, for example, it’s the original Star Wars. Episode IV: A New Hope. Imagine, in that movie as the wicked Grand Moff Tarkin baits Princess Leia into giving up the location of the hidden rebel base, under threat of destroying her home planet Alderaan.

Remember that tension as he curls, “another target, a military target, then name the system!”

Pick another movie. Think back on Chinatown as Faye Dunaway wails, “she’s my daughter.”

Think back on how Lady Macbeth manipulates her husband: “screw your courage to the sticking place.”

Now, think of every movie or play or episode of television that you’ve ever seen, and then remove from them the ability for a character to talk with another.

Imagine Romeo only speaking to us, the audience, about his love of Juliet.

Imagine Princess Leia talking to a chorus about her home world, not being able to plead with her captor to save her planet.

It makes for desolate drama: a world devoid of dialogue, but this isn’t a historical hypothetical.

Before Aeschylus: Drama Without Dialogue

In the late 400s B.C., theatre as we know it was evolving within Ancient Greek Tragedy.

Greek theatre had sprung out of religious ceremonies performed in honor of the god Dionysus (god of Wine, Theatre, and Religious Ecstasy).

These plays were recitations of stories that had just recently made a critical leap. An actor now portrayed a character in the story of a drama instead of just narrating the story.

However, even after this critical leap, plays still experienced one crucial drawback. The character only spoke to the audience or to another group, one that shared the stage. Ancient Greeks called this group of players the chorus. They would comment on the action for the audience, dance, and speak as one.

No matter the story, even the presumably conflict-laden tale of Zeus defeating the Titans, there was only ever one actor on stage. This actor delivered his lines solo.

Even with inclusion of choral performers, there was no tension. No on-stage conflict. No drama.

It is in this world that Aeschylus ignited a dramatic revolution.

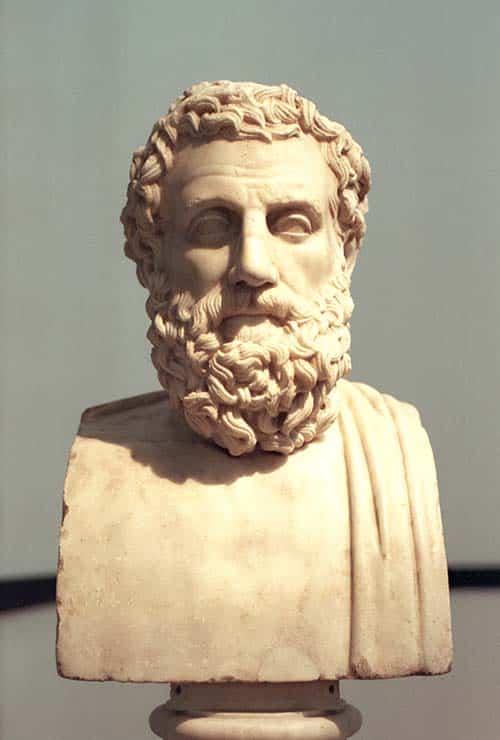

Aeschylus: Greek Dramatist, Father of Tragedy

The Greek dramatist Aeschylus was born in Eleusis, Greece around 524 BC. Aeschylus was born to the family of his father, Euphorion of Eleusis, in what was the region of Attica.

One interesting aside is that Aeschylus was supposedly initiated into the nearly apocryphal Eleusinian Mysteries. Actually, the Eleusinian Mysteries, the ancient cult-like gathering so steeped in Greek mythology and religion, may actually help explain his origin story as a playwright.

Legend has it that while working in the vineyards as a young man, Aeschylus was visited in a dream by the god Dionysus, who instructed Aeschylus to write tragedies. Upon waking, Aeschylus immediately reoriented his life to put the creation of Greek drama front and center as a playwright, thus creating the Aeschylean tragedy.

Ancient Greeks performed Aeschylus’ first play a year later in 499 BC. The newly turned playwright Aeschylus subsequently won his first tragedy competition 15 years thereafter in 484 BC.

Aeschylus’ plays from this early time period have unfortunately been lost to the passage of time. In total, only seven of his plays survived to modern times.

We don’t have access to any Aeschylus scripts until 472 BC, when Aeschylus introduced the world to The Persians, a dramatic play about The Persian Empire during their wars against Ancient Greece.

7 Surviving Plays of Aeschylus

You can find Aeschylus’ work collected in many a university press, from Cambridge to Chicago, and Chicago is doing an especially admirable job attempting to preserve these historic plays.

However, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) offers his surviving works available for free at the links provided below.

- The Persians (read)

- Seven Against Thebes (read)

- The Suppliants (read)

- The Oresteia

- Prometheus Bound (read)

We encourage you to read these plays and discover the origins of dialogue. Whether it’s through university press editions or free versions, experience the thrill of the dramatic arts ancient history.

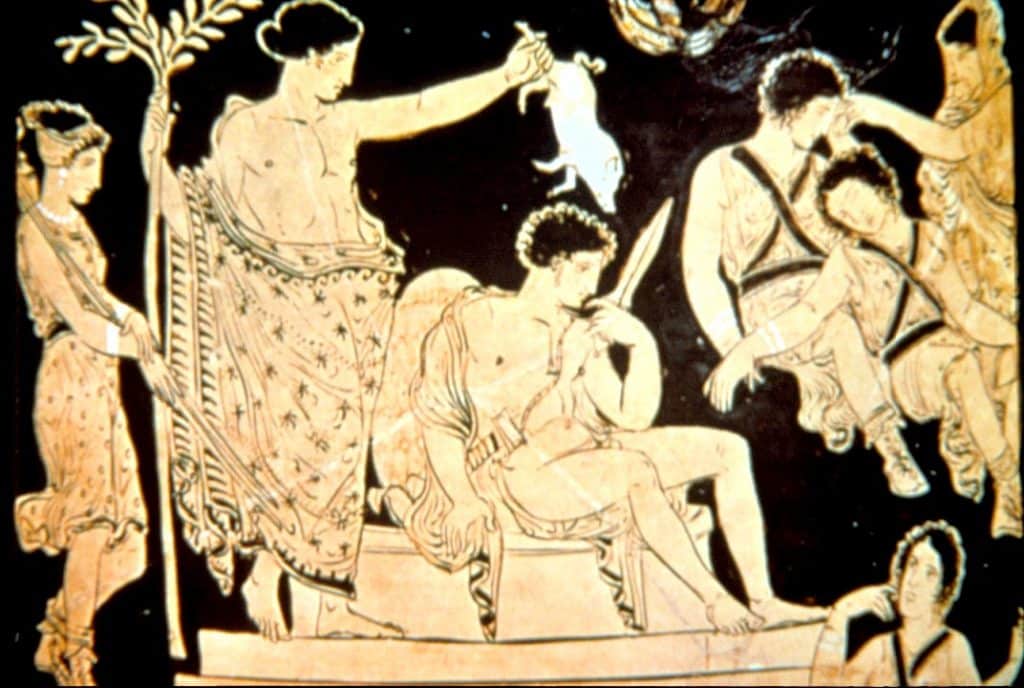

The Persians: A Greek Drama Time Capsule

The Persians is the oldest known play in the history of theatre.

Inspired partly by Aeschylus’s own experiences in the Battle of Salamis against the Persian Empire, The Persians tells the story of Queen Atossa as she confronts the ghost of her dead husband over the failure of their son, Xerxes I, in his expedition against the Greeks.

This dramatic play, The Persians, is our first known example of two characters on stage speaking with one another. It is our first textual example of dialogue.

While many of Aeschylus’ plays have been lost to history, we do know that The Persians was the second play in a trilogy. We also know that subsequent Greek historians have credited Aeschylus for the invention of dialogue.

So while we cannot say for certain that The Persians is the first instance of written dialogue between two characters, we can say that it is dialogue’s first known instance.

Regardless if dialogue first premiered in The Persians or whether it first appeared in one of history’s many plays that have been lost to time, the result is the same. The simple introduction of two characters on stage at the same time speaking to each other is perhaps the most explosive innovation (dare we say revolution) in the history of theatre.

Aeschylus: Father of Dialogue

With the simple addition of a second character to speak with a protagonist, Aeschylus fashioned a completely new dimension to theatre.

The stories theatre could tell became so much richer, so much more realistic, and so much more engrossing by taking the brave step of turning the story away from the audience and toward the players of the tragedy. In the case of Aeschylus’ plays, an Aeschylean tragedy.

The concept of dialogue seems so elementary to us today. It’s nearly unimaginable what modern pop culture would look like without the prevalence of dialogue. Nearly all of our narrative consumption involves dialogue, yet the concept is quite radical and rests upon a deep trust in the audience.

Early Greek Drama

Imagine, again, that you’re living in 500 BC. The only forms of dramatic entertainment are poetic recitation and theatre, which at the time is a quasi-religious ritualistic performance of myths and legends.

Both of these forms of entertainment involve stories that actors or performers tell you, the audience member.

An actor gets on stage and tells you a story. He sings of the victories that Cronus (Zeus’ father) won over his father, Uranus. You get it. You understand. Someone is telling you a story.

Now, imagine again, how revolutionary it would be if that same actor changed the story. Instead of him saying, “Cronus killed his father,” he said, “I am Cronus. I killed my father.”

This is a revolutionary concept if you have never experienced this before.

It’s a lie: he is not Cronus; He is an actor. The actor is challenging you to pretend and accept that he is Cronus, so that the story becomes more believable.

The Dialogue Revolution Waits…

So, now you’ve seen a couple of plays with these newfangled “actors” who pretend to be gods and kings.

You understand the concept now. They explain to you their point of view, and it makes the story all the richer.

Perhaps the actor speaks to a group of people, a chorus, who represent the collective citizens and speak as one. Perhaps this choral group speaks to you, or perhaps the chorus represents you and speaks back to the actor.

You like this. You have an intimate connection with the story, because the character speaks to you directly.

Now imagine how Earth shattering it would be when Aeschylus arrived and completely destroyed this relationship.

… The Dialogue Revolution Explodes

There you are, in the audience of Aeschylus’ newest play, The Persians.

Atossa arrives on stage and summons the ghost of her husband, King Darius. Instead of speaking to you, or instead of communicating with a narrator, she turns away from you the audience in favor of her husband.

You are no longer in communication with the Queen. Instead, you are in effect spying on her.

Queen Atossa speaks to her husband, and the challenge is on you, the listener. You and the rest of the audience must grasp the story as it is unfolding in front of you. You must be an observer as a confrontation happens before you without explanation or representation.

This is revolutionary. This is evolutionary.

The gambit clearly worked. Aeschylus went on to win thirteen Dionysia festivals, earning him the title of Father of Tragedy. While it is true that all of his extant or remaining plays are tragedies, the title of “father of tragedy” is far too narrow.

Aeschylus was the father of dialogue, which is why Aeschylus was also the father of drama.

A Brush with Aeschylus: A Personal Note

It was the summer of 2014. I was 21 years old. I had just finished my junior year at NYU studying playwriting.

My family had somehow found themselves living in Sicily outside of the small town of Motta Sant’Aanastasia, so I was home in Sicily, immersed in the history of an island that had been ruled by a succession of Greeks, Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Normans, French, Spanish, Northern Italians, Americans, and it had finally won the right to home rule.

As a lover of history, I fell in love with the island. Hard. Sicily held monuments and ruins from baroque palaces to Phoenician walls, and I wanted nothing more than to dissolve myself into the living history of the island.

In the Southeast of Sicily, the city of Siracusa (founded as an ancient Greek colony) boasted one of the most complete Greek theatres in the world. In fact, when the Greek Tyrant Hieron I was in power he brought Aeschylus to Siracusa, and Hieron used his power to produce legions of Aeschylus’ plays.

He possibly even premiered Aeschylus’ contested play, Prometheus Bound.

Prometheus Bound: A Side Note on Authorship

Some scholars contest the authorship of Prometheus Bound to this day. Its plot follows the myth of Prometheus, the Titan punished by Zeus for stealing fire from the gods and giving it away to mankind.

Scholars say Prometheus Bound represents only the first installment in a trilogy. The sequels: Prometheus Unbound and Prometheus the Fire-Bringer.

Today, it’s suspected that Aeschylus was not the author. Although, Aeschylus’ authorship is reportedly accounted for in the Great Library of Alexandria itself, some modern historians discount this due to analysis of the style and meters used in the play versus Aeschylus’ plays, as well as an unflattering depiction of Zeus.

Due to their observations, some historians place the date of Prometheus Unbound’s origin around 415 BCE. Aeschylus is thought to have died in 456 BCE, about 40 years before this newly proposed date authorship date.

Funny enough, historians believe Aeschylus’ son, Euphorion (named after his grandfather), may be the true playwright responsible for the Prometheus trilogy. Euphorion was a successful dramatic playwright in the time of Sophocles and Euripides.

We may never truly know, but Aeschylus is still considered the author of the famous text until proven otherwise.

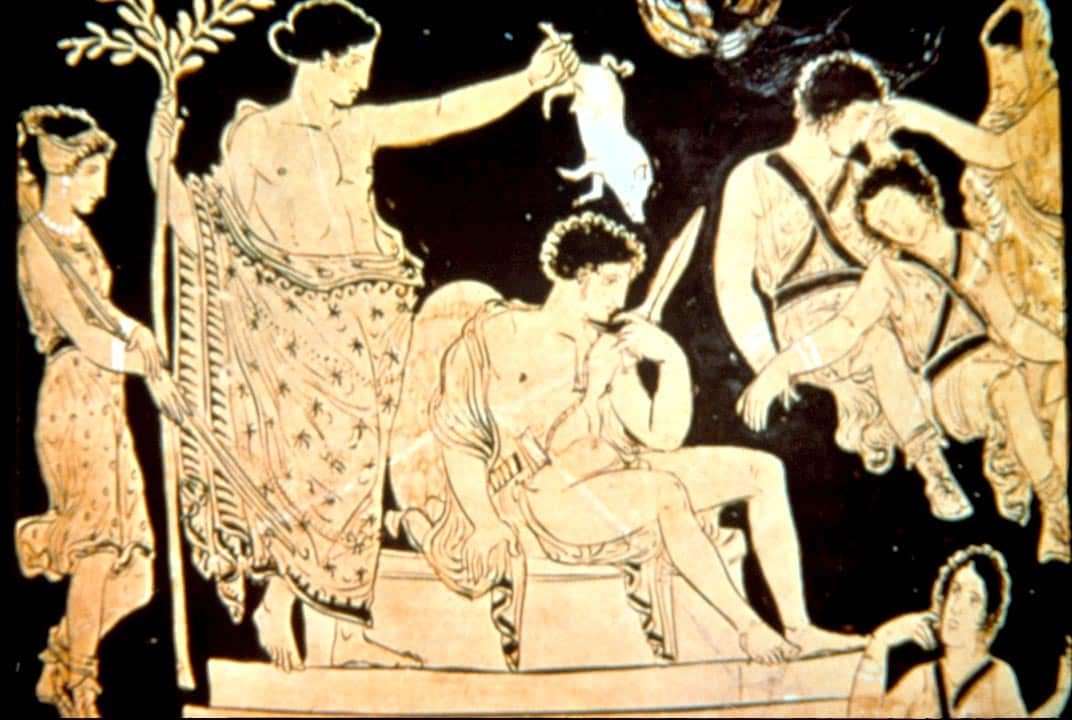

Aeschylus’ Agamemnon

Since 1914, the theatre in Siracusa had presented elaborate productions of ancient Greek tragedies and comedies, starting with Aeschylus’s Agamemnon.

In the summer of 2014, their 100th season, the theatre was producing Aeschylus’ Agamemnon.

I begged my father. Please, as a playwright and historian, please take me to see Agamemnon.

Fine. He caved.

One summer evening, we flew down the highway from Motta to Siracusa where we got two scalped tickets for Agamemnon. Scalped!

We split up and were ushered into the 2,500-year-old stone seats that were carved into the hillside. I, an Italian-sized 5 foot 8 inches, looked across the theatre to see my 6-foot-1-inch father bunched into the confines of an ancient open-air house of drama.

I owed him one.

Agamemnon Performed: The Power of Dialogue

The sun faded behind the Cyprus trees, and a massive bronze cauldron, twenty feet in the air, lit up with a brilliant flame that shone upon the dusty stage. Suddenly, I was thrown into the drama of an old king coming home after many years at war.

I was one of countless students who had studied the dramatic structure of Agamemnon. I was one of countless nobodies who had sat on these cool stone seats to see a king betrayed by his wife.

Perhaps most importantly, I was a spectator who was able to see a revolution on stage. To see the actors turn away from me and turn to each other, forcing me to observe the action as a spectator. A spy.

I waited, my back aching on the stone, for the actors to finally turn away from the chorus and to each other.

Finally, Agamemnon arrived to see his wife, Clytemnestra, where their pleasantries after years apart devolved into argument.

Clytemnestra: Would Priam victorious have ventured this service?

Agamemnon: Priam would have trashed this silk and not thought twice.

Clytemnestra: Then what have you to fear but the people’s blame?

Agamemnon by Aeschlus

Agamemnon: Dialogue Appears

After scenes of monologues and soliloquies, we finally fell into single lines of dialogue, where Agamemnon and Clytemnestra did battle through argument–a theatrical revolution.

Scenes later, Clytemnestra emerged from the bedroom, bloody sword drawn, fresh from killing her husband. She turned to her lover, Aegisthus, to speak of how Agamemnon has died by her hand, when he turned to spill more blood.

Clytemnestra restrained her lover.

Clytemnestra: No, my best of men. Enough blood’s flowed.

Agamemnon by Aeschlus

At her intervention, Aegisthus relented. Through her dialogue, through her direct confrontation with her lover, she was able to halt further bloodshed.

Recitation could not pull off this subtle dramatic dance. Perhaps only through mountainous monologues between the character and a chorus.

Instead, so much plot was able to be condensed into short but direct lines of dialogue and confrontation between two characters who had opposing desires at battle with one another.

This introduction of dialogue became revolutionary.

How Well Does Greek Drama Hold Up Today?

I’ll be honest though, as revolutionary as it was, the play seemed shockingly primitive.

It was akin to watching a recreation of man’s first fire. It was slow, inelegant, and far shorter than I had imagined. But still, it was beautiful. I had seen the first examples we have of dialogue. I had seen the revolution that had given us all forms of drama we take for granted, including countless plays.

It’s like seeing the skeleton of Lucy, the early hominid. From this skeleton, all of us are derived.

And I saw that skeleton performed in the venue where those skeletons were built.

Our Dialogue

I’m talking to you in this article. I shifted from the chorus-like we into the singular I.

I told you a story. A simple story of a student seeing the dead speak in a master class of drama.

I gave you dialogue, turning you into a spectator. And I presented this to you as something important. Something that I hope you will examine for yourself as to why it’s important and as to why I say thank you to Aeschylus.

Aeschylus, when he died, had this inscribed as his epitaph:

“Aeschylus, the Athenian, Euphorion’s son, is dead. This tomb in Gela’s cornlands covers him. His glorious valor the hallowed field of Marathon could tell, and the longhaired Persians had knowledge of it.”

Epitaph of Aeschlus

His epitaph never mentioned anything about his revolutionary acts as a dramatist.

He was buried as a soldier. It’s true that he did see battle, but none of his contributions to drama and theatre are mentioned. It’s stunning. It’s a tragedy.

Perhaps that’s why Aeschylus is best remembered as the father of tragedy and not the father of dialogue.

It is best to participate in a contest for probably the greatest blogs on the web. I’ll suggest this website!