Princess, priestess, and prophetess Cassandra of Troy lived under a terrible curse; she could see the future and had to speak the truth, but no one would ever believe her.

A character from Greek mythology, her story has fascinated audiences for thousands of years.

Who was Cassandra? Who cursed her and why? What did she do about it?

Who Was Cassandra of Troy?

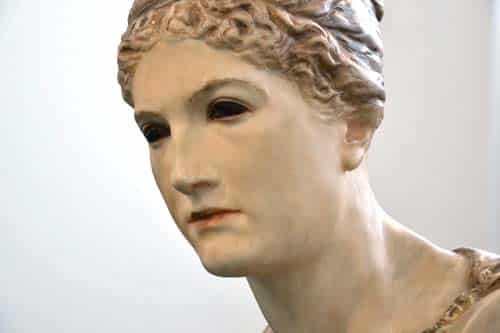

In Greek mythology, Cassandra was the daughter of King Priam, the ruler of Troy during the Trojan War, and his wife, Queen Hecuba. This made her a princess of the highest rank.

With either brown or flame-colored hair, she was considered the most beautiful of King Priam’s daughters.

About Cassandra’s personality, little is known. Although, we may conclude that she was principled, passionate, and courageous. In some versions of the myth, Cassandra is presented as chaste, in others as devious.

Most versions say that Cassandra was a priestess in the temple of the Greek god Apollo, and that she was a seer or prophetess, possessing the gift and curse of prophecy.

Almost all sources of Greek mythology say Cassandra was insane, prone to fits and mad uttering, and that this madness was the result of living under that power and its unbearable curse.

My Early Interest

As a child, I was an avid reader and devoured children’s books with retellings of ancient myths.

Cassandra’s character stood out: unlike other females, she wasn’t meek and obedient, waiting to be rescued. She had the courage to speak out, and this rebelliousness appealed to me.

In those books, the story had been adapted for children and claimed that Cassandra was cursed as punishment for her disobedience.

What was Cassandra’s Curse

In ancient Greek versions of the myth, starting with the play Agamemnon by Aeschylus,Cassandra has the ability to see accurately into the future. The curse is that no one ever believes her or her predictions, despite every prophecy being true.

As an added twist, she is also forced to always speak the truth. She can’t even trick people by telling lies or false prophecies, which they will disbelieve.

In some versions that I read in my youth, Cassandra is doomed to see only terrible things, which makes her utterances and her presence unwelcome and unpopular.

Some authors have given the curse a different spin: Cassandra is not a Seer, but a woman gifted with political acumen and common sense. What she sees in the future (e.g. the Trojan War) is what any political observer could have predicted.

Instead of a divine curse, Cassandra deals with powerful politicians who suppress the truth.

For example, in Christa Wolf‘s novel Kassandra, written during East Germany’s communist regime, Cassandra knows several truths that the government wants to suppress. She discovers and tries to reveal that Helen is not really in Troy and that preparations for a war with the Greeks are based on false claims.

But the government forces her to remain silent.

Who Cursed Cassandra & Why?

The God Apollo cursed Cassandra, Troy’s princess, because she refused to obey him. This is the part the children’s version left out: the amorous Greek god demanded erotic favors.

Ancient authors agree that Apollo desired the beautiful Cassandra and granted her the gift of prophecy in order to woo her as a lover, according to Greek mythology.

Cassandra accepted the gift of the ability to tell prophecies, but she rejected Apollo’s sexual demands.

But the same ancient authors disagree about the nature of the deal. Some (including the Latin author Hyginus in Fabulae) say that Apollo gave Cassandra prophecy as a courtship gift. When this magnificent gift didn’t sway her, the rejected suitor was angry and added the curse that Cassandra’s prophecies would never be believed.

Variations of the Myth

In some variants on this version of Greek myth, Cassandra experiences an additional dilemma. As a priestess of Apollo, she has sworn eternal chastity. Now, the Greek god himself demands her virginity. Whatever Cassandra decides in this predicament is wrong, thus furthering the tragedy of her story.

In other versions of Greek mythology, including Aeschylus’ Oresteia, Cassandra and Apollo struck a bargain: she agreed to sleep with him if he gave her the gift of prophecy. Apollo fulfilled his part of the agreement, but Cassandra reneged once granted the power.

Unable to take the gift of prophecies away, Apollo punished Cassandra the promise breaker with the curse that her words will never be believed.

Interpretations of the Rejection

In the Middle Ages, writers portrayed Cassandra as a proto-Christian prophet. She was able to see the coming of Christ, and therefore rejected the heathen god Apollo of the Greeks.

Marion Zimmer Bradley, in her novel The Firebrand, creates a different conflict of spiritual loyalties. Cassandra pledges herself as a priestess to a female goddess as well as to Apollo.

In addition. Zimmer Bradley gives a different spin to the myth’s amorous angle. A lecherous Trojan temple priest molests Cassandra, and she refuses his advances… but then realizes that this may have been the god himself in human form.

What Does Cassandra Do About the Curse?

In most tragedies, poems, and novels, Cassandra does very little beyond ranting and wailing.

She continues to shout her futile warnings, although she knows no one will believe her words.

Cassandra keeps bemoaning her cruel fate, which doesn’t change anything. She keeps beseeching Apollo to lift the curse, although he clearly has no intention to, and accusing him of unfairness, which is equally pointless.

In Friedrich Schiller‘s poem Kassandra, she moans:

Und sie schelten meine Klagen,

Und sie höhnen meinen Schmerz.

Einsam in die Wüste tragen

Muß ich mein gequältes Herz,

Von den Glücklichen gemieden

Und den Fröhlichen ein Spott!

(And they berate my wails

and they mock my pain.

I must carry my tormented heart

lonely into the desert.

Avoided by those who are happy

and mocked by the merry ones!)

Kassandra by Friedrich Schiller

And demands that he lifts the curse:

Nimm dein falsch Geschenk zurück!

(Take back your false gift!)

Kassandra by Friedrich Schiller

In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, she accuses the god who cursed her:

Apollo, Apollo!

God of all ways, but only Death’s to me,

Once and again, O thou, Destroyer named,

Thou hast destroyed me, thou, my love of old!

Agamemnon by Aeschylus

In the Euripides‘ play The Trojan Women, she is also passive but has ceased the futile ranting and wailing. She gained a dignified serenity in her resignation.

Due to her gift, she knows she’ll be murdered soon and welcomes death.

In the epic poem The Fall of Troy by Quintus Smyrnaeus, Cassandra takes physical action to avert the disaster manufactured by the Greeks.

No one listens to her words of warning that the Trojan Horse contains Greek warriors, so Cassandra grabs an ax and a burning torch and tries (unsuccessfully) to destroy the wooden horse and the Greeks inside it herself in order to save her home city.

What Happens to Cassandra After the Fall of Troy?

The ancient authors of Greek mythology agree on her fate: when the Greeks conquer the city of Troy, she gets raped by Ajax the Lesser of the Greeks, even though she has sought refuge in the temple of Athena, which is sacrosanct.

Cassandra’s rape was so brutal that in some versions of the story, the wooden statue of Athena turns its head. Even Ajax’s fellow Greeks consider punishment for the heinous rape, until he begs for forgiveness at the foot of the same statue and altar.

According to some accounts of myth, Athena later takes out her wrath against the rapist for the atrocity in the temple of Athena and its sacrilege.

Agamemnon’s Concubine

The victorious Greeks divide the spoils, and Cassandra gets allocated as concubine to the Greek King Agamemnon of Mycenae.

Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnaistra and her lover, Aegisthus, kill both Agamemnon and Cassandra.

One happy note is that ancient writers say Cassandra was deemed worthy of the Elysian Fields due to her piety.

The Elysian Fields, or Elysium, is considered the Ancient Greeks’ most honorable afterlife for those whose soul is taken to the underworld. It’s a resting place called home by only the most heroic of Greek mythology’s fabled dead.

A Second Life for Cassandra

However, later writers often reinvent myth and the fall of Troy to give Cassandra another life.

She survives the murder plot against Agamemnon, escapes the fall of Troy along with eluding her own death, and starts a new life under an assumed identity, usually in a humble role in a peaceful idyll. In Cassandra, Princess of Troy by Hillary Bailey, she finds and marries a good man and lives out her life as a wife on a quiet farm home in Thessaly.

Marion Zimmer Bradley, in The Firebrand, gives Cassandra and King Agememnon’s wife Clytemnaistra a moment of shared feminist understanding. Only King Agamemnon of Mycenae dies by his wife and her lover’s hand.

Free from Agememnon and Greek captivity, Cassandra subverts her tragedy and travels to Asia with plans to form an ideal women-ruled kingdom.

What Does Cassandra Represent?

Over the millennia, Cassandra has been put to use by writers to support their viewpoints.

Some have used the myth of Cassandra as an example of a chaste virgin because she fought to keep her herself pure. Others have held her up as an example of an evil seductress, because Cassandra used the power of her sexuality to lure Apollo.

She has been portrayed as a bad woman, because she spoke up against the decisions of powerful males instead of keeping quiet as a woman should. But she was also held up as the victim of a woman-oppressing patriarchal culture.

Older Retellings

Medieval Christians saw her variously as a proto-Christian, a true prophetess who foretold the coming of Jesus Christ, and as a martyr who suffered a terrible plight because she refused to obey the pagan God.

Yet others from the same period of history held her to be a wicked sorceress in the devil’s service because of her clairvoyance and disobedience.

Depending on whether or not she struck a deal selling her favors to Apollo, she is seen variously as a prostitute, as a contract breaker, or as as a victim of attempted sexual coercion.

Modern Interpretations

In 20th century retellings, she is a mouthpiece for political dissidents who use recourse to permitted ancient legends to issue warnings that would otherwise get ignored or to tell the stories that would otherwise be censored if not shrouded in metaphor.

Writing in 1935, Jean Girardoux uses Cassandra’s voice in his play La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu (The Trojan War Will Not Take Place) to warn audiences of the war clouds gathering over Europe.

During the Cold War period, Christa Wolf wrote Kassandra, using the long-ago happenings in Troy to alert fellow East Germans to the truths suppressed by the regime.

Cassandra, Voice of Many

As a result, Cassandra is the “voice” of many, and each of her voices has a different (and contradictory) message.

Still, audiences pay attention to what Cassandra says in novels, poems, and plays about the fall of her home.

I find this deeply ironic, because during her lifetime, her words and warnings fell on deaf ears.

Getting No Satisfaction

In my quest to make sense of Cassandra’s story, I devoured book after book: myths, novels, poems, plays.

But instead of satisfying my need, they increased my frustration. None of the versions convinced me that I was reading about the “real” Cassandra.

Of course, I understood that Cassandra was a character from myth, not based on a historical person but invented by storytellers. Still, I yearned for a literary portrait of the Trojans’ prophetic princess that felt “real.” A Cassandra I could believe in.

With every version I read, something niggled.

Not Quite the Right Cassandra

Would Cassandra really grieve at the death of Agamemnon, the man who claimed her as his share of the spoils of war and used her as a concubine? Aeschylus thinks so, but I don’t.

I loved the emotional intensity in the rousing ballad by Friedrich Schiller, my favorite German poet. But would Cassandra, after years of suffering, walk into a laurel grove and lament her fate with such emotional intensity, beseeching the god to withdraw the curse?

Such passionate anguish would be psychologically plausible if she had just come to realize the enormity of her fate. But after years of suffering, the despair would have a quieter, resigned, bitter quality, like glowing embers rather than bright flames.

Not Quite Right Reimaginings

Much as I admire the 20th century retellings with their clever use of the Trojan War plot to create a message about their own time, their versions never quite resonated with me.

They seemed to be about a woman from the authors’ world, not about Cassandra from Bronze Age Troy.

The novels bestowing on Cassandra a lover who believes her even when no one else does, or a happy ending in idyllic rural anonymity, undermine and devalue the tragedy of her fate.

The Firebrand

The novel I read most often, at least five times, was The Firebrand by Marion Zimmer Bradley. Its title and premise lured me again and again, yet each read left me unsatisfied.

Supposedly a historical novel, and well-researched in some aspects, its depiction of siege warfare in the Bronze Age is far removed from historical reality. Siege warfare in the Bronze Age is a topic I’ve studied in depth. So, when I read the novel, I spotted implausibilities and they spoiled my reading pleasure.

Siege Inaccuracies

The inhabitants of a besieged city would suffer hunger and deprivation.

After a few months, mothers would dig the earth with their fingernails, desperate for a few grubs to feed their starving children.

But in the novel, years into the siege and before the Trojan Horse, Trojan women bake pastries and sell them to the besieging soldiers. While I could believe in war profiteers, I couldn’t believe in the pastries.

I couldn’t believe in this “siege” and therefore couldn’t believe in the character either.

Cassandra the Cunning

Whichever version I read, what bothered me most was Cassandra’s passivity. A woman who, as a young girl, had the courage to defy a god, wouldn’t cower and passively bemoan her fate.

Moreover, if she had really tricked the god with a false promise, she possessed great cunning.

Wouldn’t she use her wiles to hatch a plan? In all those years of suffering, wouldn’t she plot a strategy to outwit the curse?

Giving Cassandra a Voice

So what does a writer do when she’s dissatisfied with a story? She writes her own!

I wanted to write a story about the “real” Cassandra in the “real” city of Troy. This meant sticking to the ancient sources, neither changing the plot and outcome. Nor transposing modern concerns on the ancient world.

My story would have historical authenticity. There would be no pastry-baking inside the besieged city. My Trojans would suffer from hunger, sickness, and fear.

Cassandra, in her dual role as a priestess and a member of Troy’s royal family, as daughter of her father King Priam and mother Queen Hecuba, would fare better than the commoners. She would be aware of the class privilege and have a social conscience.

A Story Emerges

Above all, I wanted to give Cassandra, the unheard, a voice. So, I chose to tell the story in first person, as her narrative. To keep the story short, I focused on one crucial moment when inner and outer conflicts escalated. The day when the Trojan Horse arrived.

I wanted a proactive Cassandra who did more than rant and wail, so I needed to devise a plot in which she played an active and decisive role. Overcoming the curse was impossible, or she would have done so long ago.

But given her cleverness and cunning, she could use the curse to her advantage.

In the classical myth, the war ends when the Greeks infiltrate the city and bring about its fall by hiding soldiers in a wooden horse, a ruse devised by the wily Odysseus. What if an equally wily Cassandra ensured its success?

Conclusion: The Real Cassandra

I’m pleased with the resulting story, blending realism and fantasy in a dark and harrowing tale. I’ve given her a voice and made her “heard” not only by her fictional compatriot but by my readers.

But is it the voice of the “real” Cassandra or am I just another writer using her to get my own message across?

I’ve received fan mail from readers who praise the story, but I can’t tell if they perceive the story the way I intended it.

Perhaps this is Cassandra’s real curse: to have many voices, none of them her own, and to be the mouthpiece of everyone while her own message remains forever unheard.

What do you think? Which stories about Cassandra of Troy have you read? What films have you seen? What is your favorite version of her tale?

Selected Bibliography

Free to Read

- Homer: Iliad (circa 800 BCE, probably based on an earlier oral storytelling tradition)

- Aeschylus: Oresteia (performed 458 BCE)

- Euripides: Troades (aka The Trojan Women) (415 BCE)

- Hyginus: Fabulae (circa 10 BCE)

- Quintus Smyrnaeus: Posthomerica (circa 490 CE)

- Herbort von Fritzlar: Liet von Troye (circa 1200)

- Friedrich Schiller: Kassandra (1802)

- Jean Giraudoux: La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu (The Trojan War Will Not Take Place) (1936)

Available on Amazon

- Christa Wolf: Kassandra (1983)

- Marion Zimmer Bradley: The Firebrand (1987)

- Hilary Bailey: Cassandra, Princess of Troy (1993)

- Rayne Hall: Prophetess. (First published in Thirty Scary Tales, 2013)

Thanks for publishing my thoughts on Cassandra! 🙂

This is a wonderful essay! Cassandra/Kassandra came into my life about 17 years ago, when I was going through a difficult time. She found me by way of the Jungian psychologists I was reading at the time, and apparently has no intention of leaving. She has become part of who I am, I identify that strongly with her. (My online name in most places is CassandraToday, including my blog.)

I’ve read many tellings of Cassandra’s story — I collect them. (I just now bought your “10 Tales” to get “Prophetess”.) Like you, I’m endlessly fascinated by how many different ways there are to tell the story. You can believe I’ll be filing away a copy of this essay for all the enticing links and references. I’m especially happy for the Schiller reference; I read German readily and enjoy opportunities to do so. I liked your translations, by the way.

I’ve read a couple of Cassandra books that you didn’t mention…

One is by an Australian writer named Kerry Greenwood. I don’t remember the title. It’s one of the retellings that bowdlerizes the tragedy that I – like you – consider the essential core of the story. Great Escape Happy Endings are fun, but I don’t read Cassandra for fun exactly.

But the good one I want to mention is Ursula Molinaro’s “The Autobiography of Cassandra, Princess & Prophetess of Troy”. It’s in a similar feminist spirit in some ways to Wolf’s Kassandra, but without the Cold War Communist layer. (It predates Wolf’s book by a couple/few years. I think the similarities may have led to a legal dispute?) Molinaro’s Cassandra declares her independence at the end, in an impassioned letter that doesn’t change Fate, hers or the cities’, but the declaration changes her. Or perhaps better said: the declaration is the culmination of her changes through the course of the novel. Fun fact: parts of the novel are written in blank verse formatted as prose. You don’t notice it at first — it kind of sneaks up on you.

I would apologize for going on at such length, but hey — I’m an old woman living alone starting my fourth month of covisolation, and I’ve found a fellow Cassandra enthusiast who invites comments. Brevity was not fated to ensue.

D’oh! Not “10 Tales”. I bought “Thirty Scary Tales”. Feel free to edit my previous comment, or post this.

I loved this article Rayne. And once again it is the strong female characters, like the Cassandra in your essay above, who are doomed to be depicted as mad “Almost all sources of Greek mythology say Cassandra was insane, prone to fits and mad uttering, and that this madness was the result of living under that power and its unbearable curse.” I love how you have woven into your essay the comments about how she used her sexuality, or not, depending on the historical interpretations.

Wouldn’t it be just something if the Marvel people who make those Wonder Woman and superhero flicks could give similar treatment to the material you have provided above. Cassandra undoubtedly got shafted by the powers that were,in her time and once again, the depiction of the woman as insane used to undermine her presence in the historical record. And why do we only hear about the great beauty, Helen of Troy. Cassandra seems far more feisty.

This is quite clever. Quite an interesting read. Her tale somehow shares a resounding similarity with The OA, a Netflix series. Would love to read Rayne’s version of Cassandra’s story.

I’m really fascinated with Cassandra’s mythology lifestyle. Although I don’t know much about her but have heard about different version of outcome writers come-up with whenever her name pops up and every version is intriguing. I really liked that you’ve given her a voice and if she ever come to life by any magical means, she would be proud of your version of telling of her curse or superpower.

This was an interesting read. I am intrigued by the myth of Cassandra and how you have finally given her a voice. I believe she had a long season of wailing and ranting as most of her warnings went unheeded by all. I do believe her real voice is now been heard. Nice writeup.

Hi, do you have any sources for Cassandra in Christian literature? I’m curious about how they portrayed her as a martyr or a devil.

A wonderfully detailed presentation of a classical myth. I think many readers end up empathizing with Cassandra especially because of the unusual curse, so in a way, her punishment is part of what defines her as a character.

I heaven’t read any of books you mentioned and analyzed Rayne, but this was really interesting. Especially the fact that curse is that no one ever believes her or her predictions, despite every prophecy being true.

She is also forced to always speak the truth. So it is a lot about not believing people that are telling nothing but the truth…Which book about her would you recommend for the beginner like me?

Apollo cursed Cassandra because she refused his erotic advances! This makes me even more invested in her story. This is such an interesting read.

This article is fascinating. Greek mythology has always been such a captivating topic to me. Thanks for bringing Cassandra’s story to life through your incredible writeup.

Cassandra is everywhere in this Pandemic world. No one is listening.

This is an amazing article, thanks a lot, I remember reading about her on Greek mythology stories when I was a teen, too.

I also thought outrageous that no one believed her, but I never thought there were so many versions about her story!