When Shakespeare’s great tragedies are brought up, including Macbeth, we often focus on literary merits, but what about plot structure?

Go to any 11th grade English class, and you’re bound to hear discussions on the symbolism of Yorick’s skull in Hamlet or the swap from iambic to trochaic in the witches’ double bubble toil and trouble.

It’s less often that we bring up the dramatic merits of structure in Shakespeare’s tragedies beyond mere labeling of its acts or turning point. That’s what makes these plays linger in our collective imaginations.

Plays on Paper: Blueprints for Productions

A close reading of Hamlet’s speak the speech can function as a staple of academic analysis for years. However, it’s not the academic merit of speak the speech that got English audiences to pay attention to Hamlet in the first place.

It’s the drama.

Shakespeare wrote plays, not books. Plays are blueprints for a production; the dialogue is intended to be read aloud.

When envisioned as a full dramatic work, the enormousness of Shakespeare’s plays becomes evident.

Hamlet runs more than 4,000 lines. At 1,000 lines an hour, it takes more than four hours for the entirety of Hamlet to be performed on the stage.

While Hamlet makes for great reading, putting the entirety of The Prince of Denmark on stage requires some creativity and a few intermissions to get the audience to the curtain call.

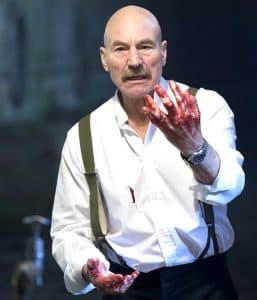

Macbeth: Lean, Mean Drama Machine

Macbeth, on the other hand, is a breeze. Clocking in around 2,400 lines, the whole play takes less than two and a half hours to stage unabridged. With minimal editing, Macbeth can clock in under 90 minutes.

Reading (or better: watching) Macbeth, you immediately get a feel for its muscular and aggressive story structure.

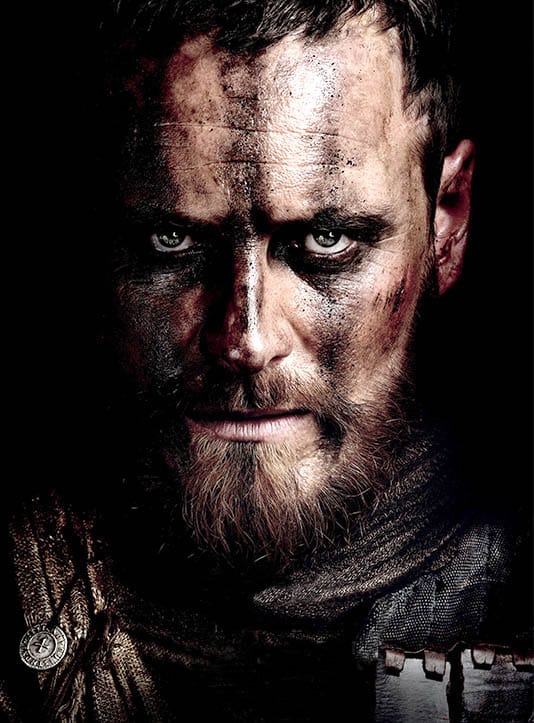

Hamlet navel gazes, Macbeth hustles. Right off the bat, in Act 1, we meet Macbeth during the aftermath of a successful war. Three witches tell Macbeth they foresee him becoming king.

Nearly immediately afterwards, we are thrust into action. Macbeth conspires with his wife, Lady Macbeth, to murder the current king, King Duncan of Scotland.

Act 2 – Act 5: A Murderous Blur

By Act 2, Macbeth kills King Duncan while King Duncan sleeps.

Bam, bam, bam.

Macbeth rolls through these plot points and with aggression. None of the events or choices feel forced, and every single action in the play comes from truthful character and circumstances.

Still, the speed at which the characters of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth move stands in stark contrast against the purposefully dawdling Hamlet.

By the final two acts, Act 4 and Act 5, the speed at which Macbeth barrels through the plot increases still.

Suddenly, we find ourselves in disparate castles throughout Scotland as murders, plots, battles, and suicides clip along at a record pace. Scenes go from breezy to brisk to there’s-no-time-left as Macduff leads his assault against the now-evil King Macbeth.

It’s action packed.

Macbeth: Model for Modern Movie Blockbusters

When Macbeth is executed properly, audiences are left in amazement. For a script so old, it somehow feels so…modern.

It feels so modern, because modern movies owe a great deal to the dramatic structure of Macbeth. Though it may be a play, thanks to its structure, Macbeth can be thought of as a proto-blockbuster.

Macbeth introduces its plot as early as Act 1.

It sets up nearly immediately that Macbeth will have to murder his mentor, King Duncan. Then, the play allows us to see the actions of its characters. The consequences play out like clockwork.

Every action comes with a natural reaction. Macbeth kills King Duncan and then has to go on a killing spree to remove any threats to his rule.

Macbeth starts the play as hesitant while Lady Macbeth is the one who urges him to act (screw your courage to the sticking place).

After the murder of King Duncan, the two characters switch tactics; Macbeth is active while Lady Macbeth increasingly withdraws.

The increasingly frenetic pace of scenes by the end of the play serves to heighten Macbeth’s tension. Shorter scenes develop urgency. Even if these sequences are playing out over hours or days

Having them

Cut

Like

This

Speeds

Up

Our

Understanding

Of

Events

(exuent)

Frenetic Pacing: Macbeth’s Action-Packed Speed

In a way, each of these scenes function as takes in a blockbuster. The faster the take, the more tension and anxiety a filmmaker can imbue into her work.

Think of the manic camera work in most war movies (1917 as the great exception). Bullets fly. Soldiers whip around. It’s chaos! The audience is on pins and needles.

So too, does Macbeth bring about this sense of urgency and tension by increasing the speed of its scenes.

What Shakespeare does that’s doubly clever is he increases the speed of these sequences at the end of the play.

In this way, the action and tension mount as the piece approaches its end. This allows the drama to push Macbeth’s plot to its climax.

Running for the Box Office

Macbeth’s climax doesn’t simply arrive; Shakespeare’s script muscles the plot and characters with speed. Thus, the climax is the peak of conflict and the peak of tempo.

Shakespeare pushes the script until it can’t possibly be any faster, any more dangerous, and that’s where he places Macbeth’s climactic end.

We call this technique running for the exit.

This technique, like William Shakespeare’s entire career, has inspired countless plays, films, and TV shows.

Movies like Alien have our lead, Ripley, literally running for her exit from an infested spacecraft. The comedy What’s Up Doc? consistently builds tension until it’s unleashed in an all out car chase across San Francisco that is as heart pounding as it is hilarious.

It’s all about building narrative momentum.

Conclusion

Macbeth excels at this narrative momentum. The play’s dramatic structure is deft and muscular, and Macbeth serves as a valuable blueprint for action movies four hundred years later.

Simply reading the script for Macbeth doesn’t allow you to fully grasp how groundbreaking it was in its fully realized form.

Go out and find a production. They’re everywhere. It’s a popular play. And as you watch from the audience, take time to appreciate how the Bard’s form inspires story craft to this day.