What better way to learn about writing novels, short stories, or any creative work than from essays on writing from legendary writers.

Whether you’re gearing up for your first run at a novel (NaNoWriMo approaches) or looking for a tune-up before embarking on your umpteenth creative writing project, you need inspiration.

May as well be inspired by the best. And maybe be taught a thing or two along the way!

Books vs Essays on Writing Fiction

Why did we choose essays?

Firstly, we certainly may write an article in the future on books from writers on writing. So, there’s no harm in leaving that topic to the side.

But chiefly, our concern is wanting to lend a hand that can be used right now. Right away. With speed.

An essay can be read in a sitting or on the way from one thing to the next, but a book is a time investment. We wanted the delivery to be quick.

Not only do we live in a fast paced world, it can be a bit of a waste to read an entire book about writing a book. Most writers would likely say you’re better off reading a great novel. Or writing one.

Not that we discourage books or any written work on the subject of writing. We don’t. But we wanted a solution for the busy working class person looking to learn the craft.

Someone with limited time but boundless spirit.

This is for you.

20 Essays from Famous Writers on Writing Fiction

We chose to not repeat authors, although quite a few writers that made this list penned multiple essays worth reading.

We picked our favorite and tried to mention the other noteworthy reads somewhere in their entry.

So, without further ado, let’s take a look at our selection of essays from writers on writing.

20) Quick Cuts: The Novel Follows Film Into a World of Fewer Words by E.L. Doctorow

E.L. Doctorow, noted essayist and author of Ragtime, is no stranger to Hollywood.

With many adaptations under his belt, including Ragtime and Billy Bathgate, Doctorow is well suited to discuss the differences between film and literature.

This essay, published in The New York Times, opines on the changes in literature since the advent of the motion picture.

Notable differences include quickening of pace, shortening of exposition, and more personal narratives.

It’s an especially fine read for anyone looking to find distinction between the disciplines of screenwriting and prose.

Brief Excerpt, “Quick Cuts: The Novel Follows Film Into a World of Fewer Words”

“Beyond that, the rise of film art is coincident with the tendency of novelists to conceive of compositions less symphonic and more solo voiced, intimate personalist work expressive of the operating consciousness. A case could be made that the novel’s steady retreat from realism is as much a result of film’s expansive record of the way the world looks as it is of the increasing sophistications of literature itself.”

E.L. Doctorow

19) The Ecstasy of Influence by Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem, author of Motherless Brooklyn, is known for his blending of multiple genres.

It only makes sense that he should write so eloquently on the power and responsibility of using influences in original work.

This essay, published originally in Harper’s Magazine, explores the challenges artists face when composing something that pays homage or outright borrows from older works.

Where does one draw the line between plagiarism and inspiration?

Brief Excerpt, “The Ecstasy of Influence”

“Blues and jazz musicians have long been enabled by a kind of ‘open source’ culture, in which pre-existing melodic fragments and larger musical frameworks are freely reworked. Technology has only multiplied the possibilities; musicians have gained the power to duplicate sounds literally rather than simply approximate them through allusion. In Seventies Jamaica, King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry deconstructed recorded music, using astonishingly primitive pre-digital hardware, creating what they called ‘versions.’ The recombinant nature of their means of production quickly spread to DJs in New York and London. Today an endless, gloriously impure, and fundamentally social process generates countless hours of music.”

Jonathan Lethem

18) Tradition and the Individual Talent by T.S. Eliot

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet T.S. Eliot, writer of The Waste Land and Four Quartets, is as known for his literary criticism and influence as an editor than for his original work.

Thus, it makes sense to include his essay on writing in a vacuum, or rather, the impossibility of such a feat. The literary equivalent of Sir Isaac Newton‘s phrase “standing upon the shoulders of giants,” Eliot’s essay actually caused quite a stir at the time.

Much like everything in the life of T.S. Eliot.

This essay, hosted now by the Poetry Foundation and originally collected in The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, nearly creates an ouroboros effect.

A “writers on writing” essay from a writer talking about writers writing on the heels of other writers.

Sorry, we couldn’t resist.

Brief Excerpt, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

“No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead. I mean this as a principle of aesthetic, not merely historical, criticism. The necessity that he shall conform, that he shall cohere, is not onesided; what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them.”

T.S. Eliot

17) On Style by Susan Sontag

Legendary essayist and activist Susan Sontag, author of In America, exudes a confident personal style.

Sontag is a bit of a Renaissance woman: professor of philosophy, journalist, novelist, playwright, photographer, and much more. To boot, she did this during divisive times, starting in the early 1960s.

It makes sense that we should pay attention to her thoughts on style, especially as she argues for its close juxtaposition to artistic norms.

In “On Style,” published in Against Interpretation and Other Essays, Sontag attempts to differentiate style from content.

Perhaps too academic for some beginners, this essay nonetheless helps to shake up preconceptions on the purpose of style in modern writing.

Brief Excerpt, “On Style”

“This means that the notion of style, generically considered, has a specific, historical meaning. It is not only that styles belong to a time and a place; and that our perception of the style of a given work of art is always charged with an awareness of the work’s historicity, its place in a chronology. Further: the visibility of styles is itself a product of historical consciousness. Were it not for departures from, or experimentation with, previous artistic norms which are known to us, we could never recognize the profile of a new style.”

Susan Sontag

16) Reflections on Writing by Henry Miller

Author of the infamously banned Tropic of Cancer, Henry Miller blurs the line between autobiography and fiction.

“Miller’s revolution, though, was not a political one,” writes Ralph B. Sipper in the Los Angeles Times’ Miller’s Tale: Henry Hits 100. “It was the wedding of his life and his art. Actual and imagined experiences became indistinguishable from each other.”

This aspect of the legend’s style lends itself well to Henry Miller’s overarching essay, a true reflection, about a life spent writing.

Brief Excerpt, “Reflections on Writing”

“I believe that one has to pass beyond the sphere and influence of art. Art is only a means to life, to the life more abundant. It is not in itself the life more abundant. It merely points the way, something which is overlooked not only by the public, but very often by the artist himself. In becoming an end it defeats itself. Most artists are defeating life by their very attempt to grapple with it. They have split the egg in two. All art, I firmly believe, will one day disappear. But the artist will remain, and life itself will become not ‘an art,’ but art, i.e., will definitely and for all time usurp the field. In any true sense we are certainly not yet alive.”

Henry Miller

15) Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale by Kate Bernheimer

Writer, editor, and critic Kate Bernheimer knows a thing or two about fairy tales.

She’s the founder and editor of the journal Fairy Tale Review, editor of numerous collections on the subject, and an author of fairy tales herself.

So, when Kate Bernheimer talks about fairy tales, you listen. Her essay “Fairy Tale is Form, Form is Fairy Tale” explores the underlying structure of fairy tales and its prevalence in much more than old Brothers Grimm stories.

Brief Excerpt, “Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale”

“Perhaps if we recognize the pleasure in form that can be derived from fairy tales, we might be able to move beyond a discussion of who has more of a claim to the ‘realistic’ or the classical in contemporary letters. An increased appreciation of the techniques in fairy tales not only forges a mutual appreciation between writers from so-called mainstream and avant-garde traditions but also, I would argue, connects all of us in the act of living.”

Kate Bernheimer

14) Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks by Joy Williams

Author of State of Grace and Pulitzer-prize finalist The Quick and the Dead, novelist, essayist, and short story writer Joy Williams could certainly be considered a writer’s writer.

It makes her especially suited to answer the age old question: why do writers write?

In her essay meditating upon the impetus to write, “Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks,” collected first in the anthology Why I Write: Thoughts on the Craft of Fiction, Williams offers several perspectives.

While there are no clear, definitive answers, burgeoning writers may find solace in the seemingly ubiquitous search for meaning.

Brief Excerpt, “Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks” by Joy Williams

“The writer doesn’t trust his enemies, of course, who are wrong about his writing, but he doesn’t trust his friends, either, who he hopes are right. The writer trusts nothing he writes—it should be too reckless and alive for that, it should be beautiful and menacing and slightly out of his control. It should want to live itself somehow. The writer dies—he can die before he dies, it happens all the time, he dies as a writer—but the work wants to live.”

Joy Williams

13) The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination by J.K. Rowling

You might say J.K. Rowling knows a thing or two about imagination.

What some casual readers–or even fans–of the Harry Potter author might not know is that Rowling faced poverty and abject failure before finding publishing success.

This combination made for the perfect 2008 commencement speech at Harvard University. Although not an essay at first, the speech became a smash hit, garnering the most views of all Harvard commencement addresses.

And, appropriately so, it was later printed as an essay/e-book titled Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and the Importance of Imagination.

Sure to inspire, and possibly soothe or reassure, the speech and resulting transcription should be read by any aspiring writer.

Brief Excerpt, “The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination”

“So why do I talk about the benefits of failure? Simply because failure meant a stripping away of the inessential. I stopped pretending to myself that I was anything other than what I was, and began to direct all my energy into finishing the only work that mattered to me. Had I really succeeded at anything else, I might never have found the determination to succeed in the one arena I believed I truly belonged. I was set free, because my greatest fear had been realised, and I was still alive, and I still had a daughter whom I adored, and I had an old typewriter and a big idea. And so rock bottom became the solid foundation on which I rebuilt my life.”

J.K. Rowling

12) Write Till You Drop by Annie Dillard

Poet, essayist, memoirist, novelist, and critic Annie Dillard has a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction to her name as well as finalist honors for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction.

Add to this a bevy of published work, “Write Till You Drop” is certainly a motto Annie Dillard lives by.

In her essay, the author of Pilgim at Tinker Creek offers up directives of great relevance for every writer. That’s because the essay’s crux, made plain in the title, is an urging to write.

Yet, the nuance of the advice is what makes this essay especially motivating and highly recommended for any writing aspirant.

Brief Excerpt, “Write Till You Drop”

“Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?”

Annie Dillard

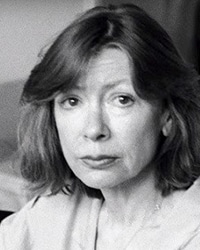

11) Why I Write by Joan Didion

National Book Award for Nonfiction winner and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Biography/Autobiography Joan Didion is a legend.

The author of The Year of Magical Thinking and Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion has been described as belonging to the school of New Journalism, which places an emphasis on narrative storytelling and literary techniques in order to communicate its facts.

As such an accomplished and versatile writer, Didion makes a singular subject for the age-old question of why do writers write.

Just like any essay on the subject, Joan Didion’s take is irreplaceably useful for writers. If for no other reason than it frames the writing pursuit as a shared experience resplendent in multiple shades and colors.

The effect being that of a warm and communal embrace.

Brief Excerpt, “Why I Write”

“When I talk about pictures in my mind I am talking, quite specifically, about images that shimmer around the edges. There used to be an illustration in every elementary psychology book showing a cat drawn by a patient in varying stages of schizophrenia. This cat had a shimmer around it. You could see the molecular structure breaking down at the very edges of the cat: the cat became the background and the background the cat, everything interacting, exchanging ions. People on hallucinogens describe the same perception of objects. I’m not a schizophrenic, nor do I take hallucinogens, but certain images do shimmer for me.”

Joan Didion

10) That Crafty Feeling by Zadie Smith

Author Zadie Smith bears nearly too many awards to count.

Beginning with White Teeth, her debut novel that took the critical world by storm, Zadie Smith established herself as one of the most noteworthy writers of the modern generation.

How appropriate then, that she spoke to the craft of writing in “That Crafty Feeling,” her lecture for students of the Columbia University writing program in March 2008. Smith later collected the speech in essay form in her book Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays.

In her essay, Smith explores many aspects of the writing process, making it a must-read for the sheer fact of learning the variances writers take to arrive at the written word.

Brief Excerpt, “That Crafty Feeling”

“Some writers won’t read a word of any novel while they’re writing their own. Not one word. They don’t even want to see the cover of a novel. As they write, the world of fiction dies: no one has ever written, no one is writing, no one will ever write again. Try to recommend a good novel to a writer of this type while he’s writing and he’ll give you a look like you just stabbed him in the heart with a kitchen knife. It’s a matter of temperament. Some writers are the kind of solo violinists who need complete silence to tune their instruments. Others want to hear every member of the orchestra—they’ll take a cue from a clarinet, from an oboe, even. I am one of those. My writing desk is covered in open novels.”

Zadie Smith

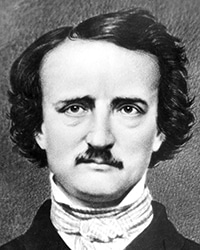

9) The Poetic Principle by Edgar Allan Poe

Legendary American poet, critic, editor, and author Edgar Allan Poe knows how to move you.

In “The Poetic Principle,” the author of The Raven and The Fall of the House of Usher breaks down exactly how he achieves this feat.

The essay is a must-read for writers not because one should necessarily follow Edgar Allan Poe’s prescription as a kind of formula.

Instead, it should serve as an example that artistic work doesn’t have to be of a purely ecstatic origin.

Writing can be a calculated affair, in part, aimed toward achieving a desired effect.

Brief Excerpt, “The Poetic Principle”

“Thus, although in a very cursory and imperfect manner, I have endeavored to convey to you my conception of the Poetic Principle. It has been my purpose to suggest that, while this Principle itself is, strictly and simply, the Human Aspiration for Supernal Beauty, the manifestation of the Principle is always found in an elevating excitement of the Soul — quite independent of that passion which is the intoxication of the Heart — or of that Truth which is the satisfaction of the Reason.”

Edgar Allan Poe

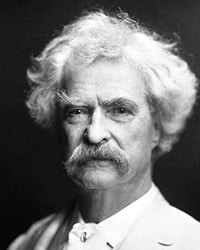

8) Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses by Mark Twain

One might call Mark Twain something of an authority on the craft of writing.

American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, earned the honorific of “father of American literature” by William Faulkner himself.

This all contributes to the fact that no one has ever been as thoroughly dragged through the mud and put on a mocking display as Fenimore Cooper.

The deed was done by Mark Twain’s own hand in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn author’s critical essay “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses.”

In what amounts to a public tar and feathering, Twain deconstructs Cooper’s writing down to the level of individual word choice.

The essay illustrates many do’s via its adamant don’ts. Not to mention the tiny bit of schadenfreude contained in Cooper’s literary trial.

Brief Excerpt, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses”

“Cooper’s word-sense was singularly dull. When a person has a poor ear for music he will flat and sharp right along without knowing it. He keeps near the tune, but is not the tune. When a person has a poor ear for words, the result is a literary flatting and sharping; you perceive what he is intending to say, but you also perceive that he does not say it. This is Cooper. He was not a word-musician. His ear was satisfied with the approximate words. I will furnish some circumstantial evidence in support of this charge.”

Mark Twain

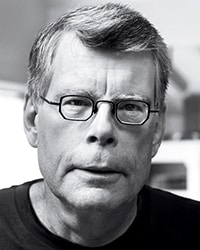

7) Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes by Stephen King

Whether you’re a fan or not, there are two undeniable facts about Stephen King. He can write like a whirlwind, and he’s successful at it.

Stephen King has penned more than 60 books, including The Stand and The Dark Tower series, and created his very own multiverse. Among other accolades, he’s received the National Medal of Arts from the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, and the National Book Foundation awarded him the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Oh, and his net worth is estimated to reside somewhere around $400 million. Plus, he’s sold more than 350 million copies of his books worldwide. A success, we’d say, even if some critics dislike him.

In addition to writing one of the most-sought books on the writing life and process, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, he’s written numerous essays. In the field of writers on writing, he’s nearly overqualified.

Seems he’s well qualified for the essay “Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes,” which out of all the essays on our list wins the prize for most enticing title.

As fans of Stephen King, we recommend you gobble up anything he has to say on the profession. But regardless, like the title says, it’s only 10 minutes long.

Brief Excerpt, “Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes”

“You want to write a story? Fine. Put away your dictionary, your encyclopedias, your World Almanac, and your thesaurus. Better yet, throw your thesaurus into the wastebasket. The only things creepier than a thesaurus are those little paperbacks college students too lazy to read the assigned novels buy around exam time. Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word. There are no exceptions to this rule.”

Stephen King

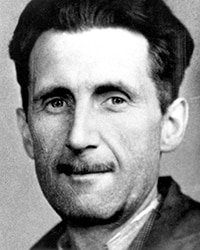

6) Why I Write by George Orwell

Legendary author Eric Arthur Blair, better known by his pen name George Orwell, stands firmly in the great pantheon of 20th century writers.

Author of 1984 and Animal Farm, one might think Orwell’s reason for writing is solely to correct societal wrongs or fight injustices.

First printed in Gangrel (Summer 1946) and later collected in Such, Such Were the Joys, Orwell’s essay “Why I Write” details his motivations to write.

Written at first as a response to an editor’s query, the essay serves as both a personal one and an objective observation of the impetus to create.

Brief Excerpt, “Why I Write”

“I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious — i.e. seriously intended — writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages.”

George Orwell

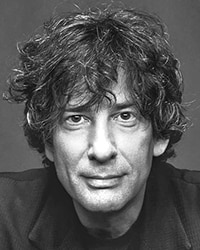

5) Where Do You Get Your Ideas? by Neil Gaiman

When one of today’s greatest originators of fresh concepts tells you that ideas are just one “small component” of writing, you listen.

Neil Gaiman, author of American Gods, The Sandman, Stardust, Coraline, and more, holds a mountain of awards. Among them, the Hugo, Nebula, and Bram Stoker awards. Not to mention a Newbery and Carnegie medal.

And Book of the Year in the British National Book Awards for The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

Written on his own blog, Neil Gaiman’s essay on where he gets his ideas answers the age-old, and somewhat frustrating, question that every writer inevitably gets.

There are no glib answers (okay, maybe a few). He shares his process with sincerity, and packages it partly in a little story, because that’s just what good writers do.

Brief Excerpt, “Where Do You Get Your Ideas?”

“The Ideas aren’t the hard bit. They’re a small component of the whole. Creating believable people who do more or less what you tell them to is much harder. And hardest by far is the process of simply sitting down and putting one word after another to construct whatever it is you’re trying to build: making it interesting, making it new.”

Neil Gaiman

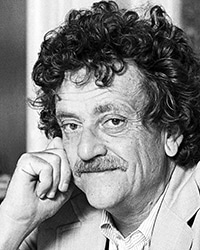

4) Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

If ever there was a writer’s writer, it’s Kurt Vonnegut Jr. When he gives advice, you listen.

The legendary literary and science fiction author, writer of Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut taught at the esteemed University of Iowa’s writer’s workshop in addition to The City College of New York and Harvard University.

It was in defense of creative writing programs and teachers everywhere that he wrote his essay, “Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists.”

Not to disparage the school of hard knocks. Quite the opposite.

Kurt Vonnegut instead shows another way of looking at creative writing instructors.

As an extension of a writer’s best friend–a good editor.

Brief Excerpt, “Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists”

“Much is known about how to tell a story, rules for sociability, for how to be a friend to a reader so the reader won’t stop reading, how to be a good date on a blind date with a total stranger.”

Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

3) Thoughts on Writing by Elizabeth Gilbert

Elizabeth Gilbert knows writing.

Author of numerous works and amazing TED Talks presenter, Gilbert is everything a writer could want to be.

She writes fiction, non-fiction, books about writing, globe trots while freelancing for magazines, and is a journalist. As of late, she’s transformed into a teacher of sorts, sharing her knowledge far and wide, and one of the leaders in the topic of writers on writing.

Her published material includes Pilgrims (Pushcart Prize winner and finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award), Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia (199 weeks on The New York Times Bestseller List and turned into a movie starring Julia Roberts), and Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (where she shares the wealth).

To say her essay, “Thoughts on Writing,” published on her own blog, is worth the time of any aspiring writer–of any form, medium, or genre–is a drastic understatement.

Brief Excerpt, “Thoughts on Writing”

“As for discipline – it’s important, but sort of over-rated. The more important virtue for a writer, I believe, is self-forgiveness. Because your writing will always disappoint you. Your laziness will always disappoint you.”

Elizabeth Gilbert

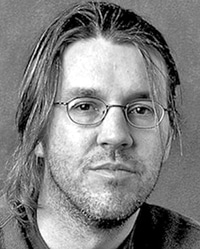

2) The Nature of the Fun by David Foster Wallace

A literary giant in the making cut short by suicidal depression, David Foster Wallace is counted among many of today’s brilliant creative minds.

Author of Infinite Jest, a novel that every intelligentsia claims to have read, although few have managed to conquer its substantial length, Wallace talked extensively about the subject of craft. As a teacher and pundit, he’s let his thoughts be known.

And for writers on writing, he’s often considered a preeminent expert on the topic.

However, “The Nature of the Fun” answers that basic question posed to nearly every writer throughout history–why do you write?

For Wallace, the answer is in surprisingly stark contrast to everything else in the tragic writer’s life.

Brief Excerpt, “The Nature of the Fun”

“In the beginning, when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor’s about fun. You don’t expect anybody else to read it. You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off. To enable your own fantasies and deviant logics and to escape or transform parts of yourself you don’t like. And it works – and it’s terrific fun. Then, if you have good luck and people seem to like what you do, and you actually start to get paid for it, and get to see your stuff professionally typeset and bound and blurbed and reviewed and even (once) being read on the a.m. subway by a pretty girl you don’t even know it seems to make it even more fun.”

David Foster Wallace

1) Not Knowing by Donald Barthelme

Donald Barthelme is almost certainly not a name you know.

Although there are exceptions, even the most devout of readers overlook the absurdist and surrealist stylings of the postmodern short story writer and teacher.

Funny, considering such eye catching titles as Sixty Stories and Forty Stories.

However, Barthelme was a regular on the pages of The New Yorker, as well as other literary magazines of his time. He even founded one–Fiction.

But don’t fret that you don’t know him. As Barthelme indicates in “Not Knowing,” his essay on the creative process, lack of knowledge can lead to invention.

That’s just one reason we recommend this for your reading list, which includes our sincere hope that you also pick up some of Barthelme’s fiction.

Brief Excerpt, “Not Knowing”

“The not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention.”

Donald Barthelme

In Closing

Writers on writing and essays on writing are almost a sub-genre in itself.

For writers out there, be careful that you don’t get sucked into the habit of consuming one diatribe after another, hoping to find eternal wisdom, without actually writing yourself.

It can be alluring, to soak in the soup of published authors, to feel like you’re holding conversations with the greatest minds. Afterall, for some aspiring writers, it’s the end goal of getting published. However, one must start with the actual writing itself, so don’t dawdle too long.

Of course, we hope that these relatively short essays won’t keep you for long. And they’re just meaty enough to be satiating.

Now, get to writing! (including dropping into the comments to share your own writing advice)